When I talk with groups about water, here are some factoids that usually surprise:

- By 2020, California will face a shortfall of fresh water as great as the amount that all of its cities and towns together are consuming today.

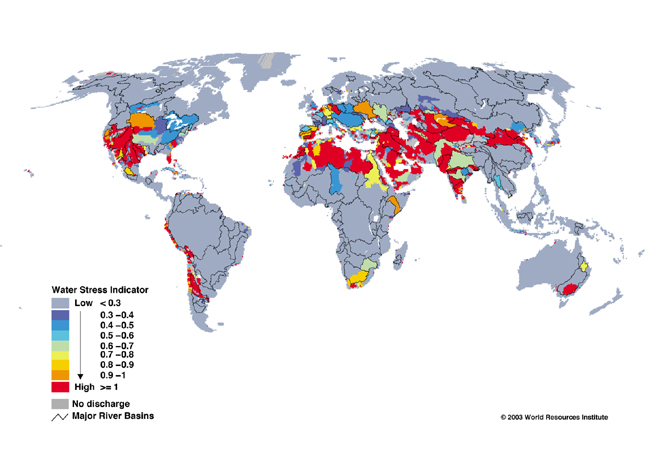

- By 2025, 1.8 billion people will live in conditions of absolute water scarcity, and 65 percent of the worlds population will be water stressed.

- To grow a ton of wheat uses 1,000 tons of water. The US is the largest exporter of wheat to the world. When we export a ton of our wheat, we are effectively including 1,000 tons of water in the bargain.

- In the US, 21 percent of irrigation is achieved by pumping groundwater at rates that exceed the water supplies ability to recharge.

- There are 66 golf courses in Palm Springs. On average, they each consume over a million gallons of water per day.

- Lake Meade (the source of 95% of water for Las Vegas) will be dry in the next 4 to 10 years (see picture below).

Water scarcity is a global problem and is not confined to “poor” nations.

In the US, we are now seeing headlines about droughts in places like Florida, Georgia, etc. – not your traditional areas of drought. A powerful way to understand the pervasiveness of America’s water scarcity problem is through the following pictures.

This first picture shows areas of the US that are experiencing moderate (yellow), severe (red), and extreme (purple) drought.

The picture above is constantly updated, and now, in fall 2011, Texas is experience unprecedented drought. I was driving through Texas a few weeks ago, and at that time, local radio stations talked about how Austin, as just one example, had experienced 72 days in a row of 100 plus temperatures. Here’s a picture of the current (September 27, 2011) drought situation throughout the US. Note that drought levels in most of Texas are at level D4 – “Exceptional.”

These dry conditions have fostered endless fires that are sweeping across Texas and throughout the Southwest. Predictions are that the drought will likely last for years. Planners will need to make sure public policy on water conservation are in line with emerging water scarcity conditions. When does a drought become a desert?

Shifting the lens toward the Southwest, here’s a picture of Lake Meade, boating haven and water source for Las Vegas. Current estimates predict it will be dry in the next 4 to 10 years.

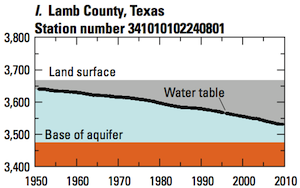

Food production in the “breadbasket” of the US depends on water from the Ogallala Aquifer. The picture below shows where the sharpest declines in water level are occurring.

The USGS monitors over 9,000 wells throughout the aquifer. Zeroing in on Texas again, here’s a picture of a typical well in Lamb County, Texas. Monitoring of this well started in about 1950, when irrigation began. This well shows a water table that has fallen steadily, and at current draw rates, this well will be dry in the next decade or so. How will farmers, who depend on a reliable source of water to grow crops and ride through accelerating drought, stay in business? How will the drying of the Ogallala Aquifer effect America’s ability to feed the nation?

A recent article in The Texas Tribune sets out the impact Ogallala water scarcity will have on Texas. This story is not unique and is being played out throughout the 8 state region covered by the Ogallala.

Highlights of the Tribune article:

- The Ogalala aquifer stretches across 8 states and accounts for 40 percent of water used in Texas.

- The Ogallala’s volume will fall a staggering 52 percent between 2010 and 2060.

- The use of big pivot irrigation — the lifeblood of the Panhandle — could be cut back severely in 10 to 20 years.

- Texans are probably pumping the Ogallala at about six times the rate of recharge.

- Water conservation and regulation policy is difficult to implement because Texas views groundwater as essentially a property right.

- T. Boone Pickens business Mesa Water and other companies are buying up water rights, and looking to market water to cities like Dallas. This is creating a variety of court challenges in the struggle to define the line between public and private water rights.

For more information on the critical issues around private and public access to water, read the well-researched Blue Gold by Maude Barlow and Tony Clarke.

MJBower says:

So glad I found this. My grandmother worked for years to help the water board of Kansas monitor drops in the water table. It’s important to note that rain does not help the aquifer replenish itself. This is deep in the ground, we’re essentially mining our water in the midwest. It is not a renewable resource. The food we produce goes out to hundreds of destabilized, developing countries. Without a productive breadbasket in the U.S., millions could starve. That makes public water rights a necessity, in my opinion.

jaykimball says:

Thanks MJ.

You are so right – the water in the aquifer is fossil. Once gone, it is gone for good. The Midwest will need to rethink their irrigation strategies. And we need to be developing a new sense of the true value of water. How much is it really worth? Something so basic to our wellbeing is surely worth more than currently paid.

In California, they see the writing on the wall – with dwindling snow pack and run-off – and are investing $6 billion to build water storage systems. No longer can they rely on water being stored in the mountains as snow, and giving it back slowly over the summer.

jaykimball says:

This article, based on research from University of Arizona is worth a read. Talks about a 60 year drought developing in the Southwest US, intensified by increased temperatures, due to climate change.

http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2010-12/uoa-hwd120910.php

BH says:

The longterm trend of the American population shifting to the sunbelt will have to reverse, as those parts of the country won’t be able to support nearly as many people in the future. Luckily, there’s plenty of space back in the rustbelt, including cities like Detroit and others that have lost half of their populations (or more). That means lots of houses, buildings and lots that are currently abandoned will have the chance to be repopulated, and with much infrastructure already in place, it’ll be relatively efficient to rebuild.

Ag_compete says:

Is it possible to replenish aquifiers by diverting extra water back down through tubes, in effect the opposite of pumping?

jaykimball says:

Great question. Don’t know.

One of the nice things about aquifers and springs is that the water is generally clean and untainted by modern surface pollutants. The water perks down through the soil and minerals and is filtered.

Seems like pumping the aquifer – if it was possible – would require some sort of filtration to make sure the safety of the potable water is not compromised. I suspect there would be some public safety regulations that relate to all that.

Sierra9093 says:

Can’t we take some of this flood water and re-channel it to the Ogallala Aquifer and other aquifers instead of watching it go down the continental drain, along with peoples homes and cars.

Rob says:

“To grow a ton of wheat uses 1,000 tons of water. The US is the largest exporter of wheat to the world. When we export a ton of our wheat, we are effectively including 100 tons of water in the bargain.” says Jay Jimball, above.

So which figure of Kimball’s is right: does it take 1000 tons of water to grow a ton of wheat, or 100 tons of water?

Makes one wonder about the accuracy of the rest of his info.

Best Regards and Good Luck U.S., with our crooked, paid-off politicians.

ejkrbc@aol.com

Shokan, NY

Rob says:

Sure, you could pump all the floodwater and storm overflow into the aquifers, and pollute them all with the toxins in the flood water and runoff – doesn’t work!

Best Regards,

Rob

ejkrbc@aol.com

jaykimball says:

Thanks for catching that. The correct figure is 1,000 tons of water to grow 1 ton of wheat.

Informed says:

Science needs to keep up with reality of water declines. I have heard there are many promising seeds being produced that will produce crops (corn, wheat, etc) for far less water than is needed today. Crop technology will save the breadbasket. We need to be able to grow corn in areas that produce 10 inches annual rainfall instead of relying on irrigation. Normally it takes about 25 inches or more of annual rainfall to produce corn.

Technology will also result in row crops that can be grown in marginal soil types.

Brina says:

That is a riduculous statement to make. When you export a ton of wheat, since wheat will store good at about 13% moisture. you are exporting 260 lbs of water. The water that the wheat grew with was put back into the atmosphere in the water cycle to provide rain or snow somewhere else.

jaykimball says:

Hi Brina, Thanks for the reply.

Not so. It’s a common misunderstanding, left over from a time when potable water was abundant.

When you fly over the midwest, you see all those crop circles? That’s irrigation, much of it from aquifers, which don’t recharge. That’s why Ag is the big drain on aquifers and water levels are falling fast.

When China buys grain from us, that’s water they avoid consuming from their own resources for irrigating thirsty crops. Rainfall is very different. It doesn’t happen when you want it, and quite often, when it happens, it happens at amounts that can damage crops and cause flooding. Drawing on underground water allows for irrigation on demand.

As national water shortages have increased, farmers have been required to curtail irrigation. Looking to the skies can be futile, as any farmer will tell you. States are now investing billions in water storage to capture runoff, for use during dry seasons. Things are changing rapidly, and our old habits of squandering water will no longer sustain.

Yes, much of the water used on crops goes into the atmosphere, but that is not a good thing when viewed as potable underground water being sent into the atmosphere, and away from areas that need water. Water also goes down rivers, collecting contaminants, pesticides, pollutions, etc. on the way. And washing away precious soil. For more on that, see the excellent report just released called Losing Ground: http://www.ewg.org/losingground/

And for more on extreme rain, see: http://8020vision.com/2010/09/11/extreme-rain/

jaykimball says:

Updated report on US water scarcity trends:

http://www.usbr.gov/climate/SECURE/docs/SECUREWaterReport.pdf

fireart says:

There are strict laws with $10,000 fines against polluting the ground water in some states.

B.VASUDEVAM says:

It is definitely possible to supply water to the full requirement to the places where there is scarcity as

rain gives to the maximum requirement in U.S.A. As a civil engineer having 40 years experience I

can challenge to do the same. B.VASUDEVAN South India Ph. 9941317411

jaykimball says:

Thanks for the comment. Would you talk about how you would do that? For example, the Southwest US is becoming a desert. Major agricultural and urban areas in the region require massive water capacity. Current infrastructure depends on water running through rivers and canals from snowpack in mountains, and that snowpack is trending down, as the globe warms.

Though rain and extreme rain events are increasing, how would you engineer a system to move water from the rainy regions, to the dry regions? What do you estimate it would cost? For example, California is very concerned about the dwindling snowpack, and has invested over $5 billion to build water storage systems to capture runoff from winter rain and rapid spring melt. No question that solutions can be engineered – but at what cost, and will it be enough?

I welcome your ideas. As the globe continues to heat, water solutions will become increasingly invaluable.

Butthole says:

boner boner boner boner boner boner boner boner boner boner boner boner boner boner boner boner boner boner boner boner boner boner boner boner

Anonymous says:

Will this not require an entirely different way of growing crops and the types of crops grown in areas of greatest stress? This for sure is a global crisis, especially with pollution and climate change now effecting water availability which is in turn effecting agriculture. How do you effectively bring such an important crisis into the consciousness of people who take water for granted?

jaykimball says:

Janearther: “How do you effectively bring such an important crisis into the consciousness of people who take water for granted?”

Spread the word, forward the link, like on facebook, tweet, tell stories, read more about water issues. Make sure schools are covering the topic, the way they did in the 70s with recycling…

Anonymous says:

Thanks. And I do blog on water issues and do what I can to spread the word about this. I believe we are in for a rude awakening.

Tossaway says:

We have a “tragedy of the commons” situation here. What we need is *more* private water rights. People will pr0tect what they have a personal ownership stake in, whereas they tend to view as “somebody else’s” responsibility problems with common property. Anyone who disagrees is free to provide verifiable evidence that they put as much direct, personal effort into caring for and maintaining public mass transit like the bus or the subway as they do their own vehicle. Paying taxes is not a direct, personal effort.

jaykimball says:

Hi Tossaway,

Thanks for your comments. Seems like you are talking about needing two things:

1. More private water rights, and

2. Less taxes

Some questions:

With regard to private water rights, since most consumers are on public water systems, how do you see converting those systems to private systems? How will a home owner or apartment dweller manage that private system? I am wondering if most people even have time to do that, and perhaps they appreciate having utilities do it for them, making sure safe reliable water is delivered to the tap.

With regard to taxes, what water related taxes are you referring to? How would people pay for their “private” water?

One of the most effective was to temper consumption is through price. Using supply and demand economics, when supply is short, or demand is high, price rises. We see this with things like gasoline and fresh fish. As fisheries are over-fished, supply drops, and prices rise accordingly. As forest are over harvested, wood supply dwindles, and prices rise.

As water is increasingly precious, we should expect the price to rise. As the price rises, people will find new ways to conserve.

Tossaway says:

I wasn’t referring to any water-related taxes. Too many people, when asked to help with something that involves charity, like indigent medical care, refer to the taxes they pay. Paying taxes might allow the government to do an inadequate job of something, but it isn’t a direct, personal effort. Thus, paying taxes for *anything* is not a substitute for personal involvement. In the context I was using, because water is too often treated as owned in common and any attempt to claim individual ownership is treated poorly, as if the person making the claim was evil or greedy, we have a situation where *nobody* claims responsibility. Personal responsibility can be avoided because “that’s what I pay taxes for.” In the area where I live, I do in fact pay a water-related tax. Florida is divided into water management districts, which have taxing authority. I will also point out that these are the same “Sweet Old Boys” who, at the same time they were demanding people cut back on water use, INCREASED the minimum allowable residential well size to ensure GREATER flow. So government service is not only NOT necessarily better, it can act directly against the public interest even while believing its actions are good, in part because there’s no real consequence. They hardly ever get fired, they just get a desk job if they are close to retirement. While I think we do need less taxes, the amount of the tax is not relevent to the point I was making.

As to public water systems, people are on them because the law requires it, not because they had a choice. I’ve lived in places where my parents were informed that they would be connecting to a public water system at their cost, even though our well and septic system was working perfectly, because it was necessary to justify the cost of the public system. If someone wants to hook up to a public system, so much the better. It might not be possible to develop a private system inside an area of dense development, like the inner city. I see nothing wrong with someone *choosing* to use a public utility for water; most problems with public water systems could be resolved if they weren’t monopolies. If a *private* competitive company were deliving the water and handling the waste, there would be better response and almost certainly a lower price. But that would mean the government water officials couldn’t protect their jobs. Ways have been developed to allow direct competition for home electric power, and something similar could be developed for water and sewer. However, because of the fixation on the idea that, as an “essential service” it can’t be privatized or that it’s “wrong” to profit from it, people tolerate poor service and middling quality water from the government. Monopolies, even government ones, have no incentive to behave benevolently or provide good service. You *have* to take crap from them; after all, what are you gonna do if you want to flush your toilet and you’re hooked up to a public system?

As to price, the price to me for the water coming out of my well is essentially zero. I don’t need price as an incentive. I conserve what I can because I believe it’s in my best interest. If I purchased water rights to ensure my own future access, I would have a strong incentive to ensure those rights are protected by stopping anyone from taking my water. Right now, I have no power to do that because it’s treated as a common resource, so if I see someone wasting water all I can do is complain openly and hope to annoy the water waster enough to stop. If I actually owned the water rights, I would be able to legally enforce action. So, if a Texas farmer owned the rights to a certain amount of water, and couldn’t get that amount because a neighbor was using more than the rights the neighbor owned, then the farmer could have an enforceable right in court, and could move faster than the government. Also, price would come into play because that right could be divided and sold. If the farmer needed more water, he could buy the right from someone else, just as he could sell if he needed the money. The farmer would have a financial incentive to use sustainable practices so that he could then have excess water rights to sell. This can be done on a free market basis with no need for government involvement other than to provide an enforcement mechanism. This method would also provide direct, personal involvement and so would likely bring a better result for everyone than you would get from a bureaucratic one-size-fits-all edict.

jaykimball says:

Here’s a good article on water scarcity in Texas.

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/07/sunday-review/getting-serious-about-a-texas-size-drought.html?nl=todaysheadlines&emc=edit_th_20130407&_r=0

A quote at the end says it all: Wes Perry, an oilman who doubles as Midland’s mayor, put it this way recently: as valuable as oil and gas are, he said, “we are worthless without water.”