Peñon de los Banos, is a women-owned sustainable organic farm cooperative, a short ride from the mountain town of San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. My wife and I are part of a field trip, organized by The Center for Global Justice, visiting the Campo, to learn more about their work.

Residents of this small dairy farm have been part of a traditional ejido system for generations. Ejidos are communal lands, for growing food, shared and co-managed by the people of the community. The system was developed during ancient Aztec rule of Mexico. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) has forced the Mexican government to do away with the ejido system, and open the land up to foreign agri-business.

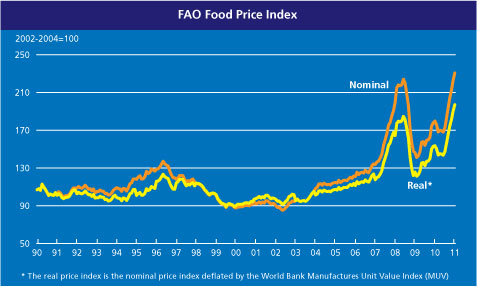

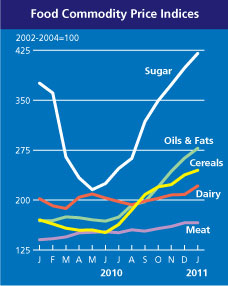

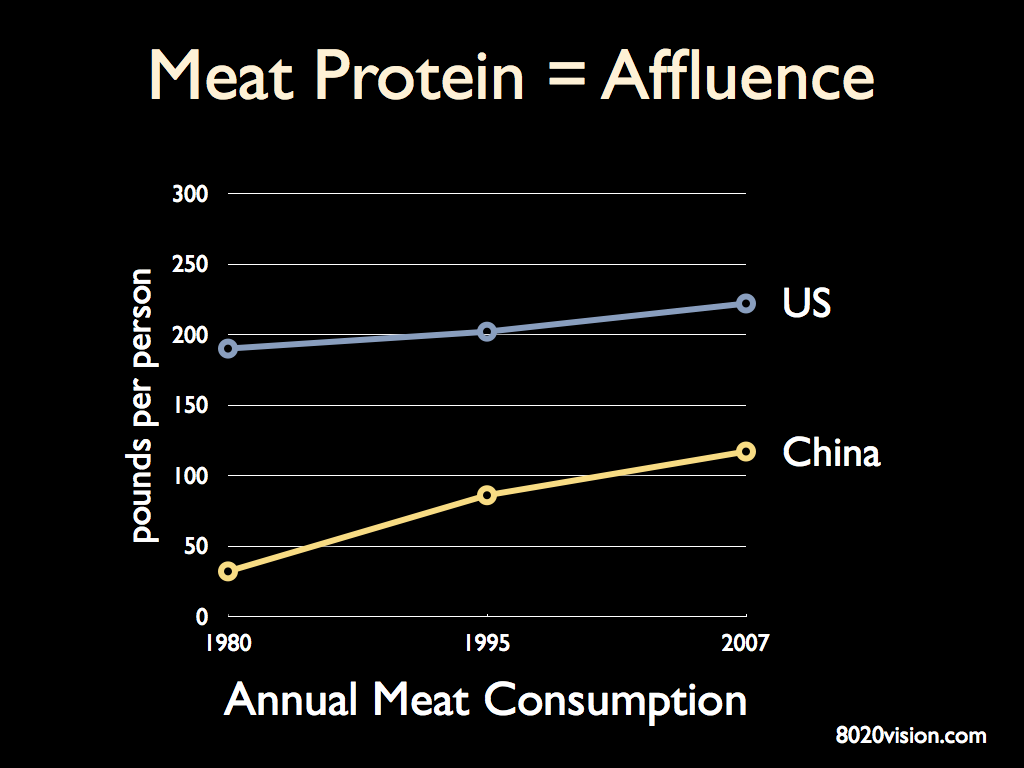

With exponential population growth driving increasing demand for food, food prices are increasing. Farm land has become a growth investment. Foreign investors are eager to buy up land in this fertile region. This can put land ownership out of reach for local farmers. Much of the traditional farming is now being forced out, replaced by industrial agriculture. So, the women of Peñon de los Banos have banded together and formed a SPR (Sociedad de Produccion Rural). Adding to their dairy cow farm, they have constructed nine greenhouses to grow organic tomatoes and other vegetables, year round. They endeavor to farm sustainably, using composted manure from their cows to keep the soil fertile, and employing drip irrigation to conserve precious water. They are creating value-added products including tomato sauce and paste.

If they can grow the farm business, they hope to bring their husbands into the operation. To help pay the bills, the spouses have had to leave the community, to work in San Miguel or the US.

They are surrounded by industrial farming, which presents some challenges. The industrial farming methods use old fashioned wasteful irrigation techniques. Peñon de los Banos uses very efficient drip irrigation, but they are drawing from the same well and aquifer as the industrial farms, so if the industrial farms run the well aquifer dry, it effects Peñon de los Banos too. And with increased drought in the south, water is getting very scarce. Also, the industrial farms are not organic, and when they spray with pesticides, the women at Peñon de los Banos need to quickly cover their crops so the poisons don’t settle on the crops.

This trip has a special energy, as we were accompanied by a wonderful bunch of young women and their teachers, from Edgewood College, in Madison, Wisconsin. The students are here on a trip lead by their sociology professor, Julie Whitaker. They are a fantastic bunch of people. Julie and I talk about sustainable farming challenges facing farmers. She seems like a great teacher. Her students ask great questions. I continue to be impressed with the social engagement and energy young people are bringing to our world. These students rock! They have it in them to leave the world a better place.

After the tour, the women of the farm serve us a delicious traditional lunch (comida). They teach me how to make gorditas, toasting them on a wood fire heated steel plate. I am frankly overwhelmed by their beautiful generous spirit. For me, this has been the highlight of my month in Mexico.

Here is a video interview with the women of Peñon de los Banos, pictures from the trip, and an audio presentation by Cliff Durand of The Center for Global Justice. Cliff talks about the history of Peñon de los Banos and small farming in Mexico, and talks about the recent impact NAFTA is having on small farmers.

Video – filmed at Peñon de los Banos

Includes video of traditional mid-day meal (comida) and interview with the women that run the farm cooperative. Translation is provided by Ousia Whitaker-DeVault.

Pictures – from around Peñon de los Banos

Scenes from the farm, sharing a mid-day meal, and at the organic farmers market

Audio Presentation: Small farming in Mexico

Cliff Durand, of The Center for Global Justice gives background on small farms in Mexico and the effects of NAFTA. Audio quality is low until about 1 minute 30 seconds. Duration: 57 minutes.