Keywords: peak oil, Der Spiegel, German military study, energy crisis

Though governments have for decades pondered the looming peak in oil production, we rarely get a glimpse into their uncut analysis.

A study by a German military think tank has analyzed how “peak oil” might change the global economy. The internal draft document — leaked on the Internet — shows for the first time how carefully the German government has considered a potential energy crisis.

German newspaper Der Spiegel reports on the study. Highlights are below, along with a translation of the document by The Oil Drum.

Peak oil is the point in time when the maximum rate of global petroleum extraction is reached, after which the rate of production enters terminal decline. As oil supply declines, in the presence of rising global demand, price will rise rapidly. Estimates vary on when we hit peak. Some say we are at peak now, some studies suggest 2014, 2020 and beyond. More on this in a future post.

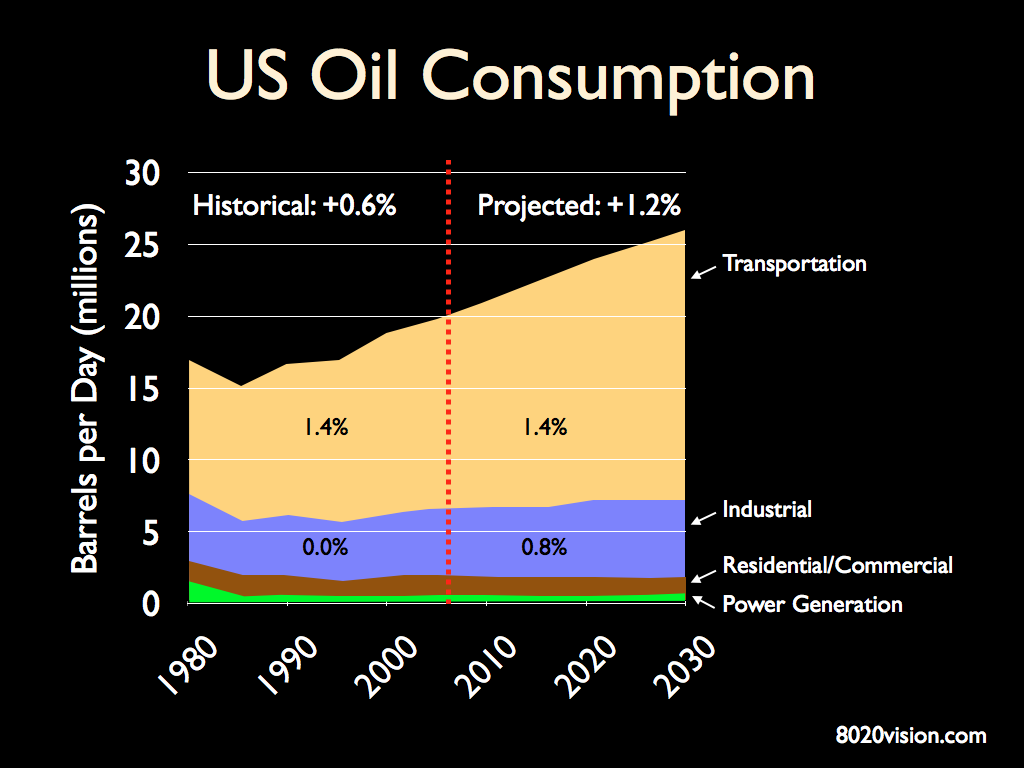

Though the global recession has slowed growth and taken the pressure off the rate of growth of oil consumption, as growth returns, so will increased consumption of oil. There is an opportunity – now – to invest in renewables, and flatten what was a rising demand for oil. And in so doing, reduce the amount of CO2 we emit, reduce our dependency on imported oil, and add jobs in the emerging cleantech renewables industries.

Highlights of Der Spiegel article Military Study Warns of a Potentially Drastic Oil Crisis

The term “peak oil” is used by energy experts to refer to a point in time when global oil reserves pass their zenith and production gradually begins to decline. This would result in a permanent supply crisis — and fear of it can trigger turbulence in commodity markets and on stock exchanges.

The issue is so politically explosive that it’s remarkable when an institution like the Bundeswehr, the German military, uses the term “peak oil” at all. But a military study currently circulating on the German blogosphere goes even further.

The study is a product of the Future Analysis department of the Bundeswehr Transformation Center, a think tank tasked with fixing a direction for the German military. The team of authors, led by Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Will, uses sometimes-dramatic language to depict the consequences of an irreversible depletion of raw materials. It warns of shifts in the global balance of power, of the formation of new relationships based on interdependency, of a decline in importance of the western industrial nations, of the “total collapse of the markets” and of serious political and economic crises.

The study, whose authenticity was confirmed to SPIEGEL ONLINE by sources in government circles, was not meant for publication. The document is said to be in draft stage and to consist solely of scientific opinion, which has not yet been edited by the Defense Ministry and other government bodies.

The lead author, Will, has declined to comment on the study. It remains doubtful that either the Bundeswehr or the German government would have consented to publish the document in its current form. But the study does show how intensively the German government has engaged with the question of peak oil.

Parallels to activities in the UK

The leak has parallels with recent reports from the UK. Only last week the Guardian newspaper reported that the British Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) is keeping documents secret which show the UK government is far more concerned about an impending supply crisis than it cares to admit.

According to the Guardian, the DECC, the Bank of England and the British Ministry of Defence are working alongside industry representatives to develop a crisis plan to deal with possible shortfalls in energy supply. Inquiries made by Britain’s so-called peak oil workshops to energy experts have been seen by SPIEGEL ONLINE. A DECC spokeswoman sought to play down the process, telling the Guardian the enquiries were “routine” and had no political implications.

The Bundeswehr study may not have immediate political consequences, either, but it shows that the German government fears shortages could quickly arise.

A Litany of Market Failures

According to the German report, there is “some probability that peak oil will occur around the year 2010 and that the impact on security is expected to be felt 15 to 30 years later.” The Bundeswehr prediction is consistent with those of well-known scientists who assume global oil production has either already passed its peak or will do so this year.

Market Failures and International Chain Reactions

The political and economic impacts of peak oil on Germany have now been studied for the first time in depth. The crude oil expert Steffen Bukold has evaluated and summarized the findings of the Bundeswehr study. Here is an overview of the central points:

- Oil will determine power: The Bundeswehr Transformation Center writes that oil will become one decisive factor in determining the new landscape of international relations: “The relative importance of the oil-producing nations in the international system is growing. These nations are using the advantages resulting from this to expand the scope of their domestic and foreign policies and establish themselves as a new or resurgent regional, or in some cases even global leading powers.”

- Increasing importance of oil exporters: For importers of oil more competition for resources will mean an increase in the number of nations competing for favor with oil-producing nations. For the latter this opens up a window of opportunity which can be used to implement political, economic or ideological aims. As this window of time will only be open for a limited period, “this could result in a more aggressive assertion of national interests on the part of the oil-producing nations.”

- Politics in place of the market: The Bundeswehr Transformation Center expects that a supply crisis would roll back the liberalization of the energy market. “The proportion of oil traded on the global, freely accessible oil market will diminish as more oil is traded through bi-national contracts,” the study states. In the long run, the study goes on, the global oil market, will only be able to follow the laws of the free market in a restricted way. “Bilateral, conditioned supply agreements and privileged partnerships, such as those seen prior to the oil crises of the 1970s, will once again come to the fore.”

- Market failures: The authors paint a bleak picture of the consequences resulting from a shortage of petroleum. As the transportation of goods depends on crude oil, international trade could be subject to colossal tax hikes. “Shortages in the supply of vital goods could arise” as a result, for example in food supplies. Oil is used directly or indirectly in the production of 95 percent of all industrial goods. Price shocks could therefore be seen in almost any industry and throughout all stages of the industrial supply chain. “In the medium term the global economic system and every market-oriented national economy would collapse.”

- Relapse into planned economy: Since virtually all economic sectors rely heavily on oil, peak oil could lead to a “partial or complete failure of markets,” says the study. “A conceivable alternative would be government rationing and the allocation of important goods or the setting of production schedules and other short-term coercive measures to replace market-based mechanisms in times of crisis.”

- Global chain reaction: “A restructuring of oil supplies will not be equally possible in all regions before the onset of peak oil,” says the study. “It is likely that a large number of states will not be in a position to make the necessary investments in time,” or with “sufficient magnitude.” If there were economic crashes in some regions of the world, Germany could be affected. Germany would not escape the crises of other countries, because it’s so tightly integrated into the global economy.

- Crisis of political legitimacy: The Bundeswehr study also raises fears for the survival of democracy itself. Parts of the population could perceive the upheaval triggered by peak oil “as a general systemic crisis.” This would create “room for ideological and extremist alternatives to existing forms of government.” Fragmentation of the affected population is likely and could “in extreme cases lead to open conflict.”

The scenarios outlined by the Bundeswehr Transformation Center are drastic. Even more explosive politically are recommendations to the government that the energy experts have put forward based on these scenarios. They argue that “states dependent on oil imports” will be forced to “show more pragmatism toward oil-producing states in their foreign policy.” Political priorities will have to be somewhat subordinated, they claim, to the overriding concern of securing energy supplies.

For example: Germany would have to be more flexible in relation toward Russia’s foreign policy objectives. It would also have to show more restraint in its foreign policy toward Israel, to avoid alienating Arab oil-producing nations. Unconditional support for Israel and its right to exist is currently a cornerstone of German foreign policy.

The relationship with Russia, in particular, is of fundamental importance for German access to oil and gas, the study says. “For Germany, this involves a balancing act between stable and privileged relations with Russia and the sensitivities of (Germany’s) eastern neighbors.” In other words, Germany, if it wants to guarantee its own energy security, should be accommodating in relation to Moscow’s foreign policy objectives, even if it means risking damage to its relations with Poland and other Eastern European states.

Peak oil would also have profound consequences for Berlin’s posture toward the Middle East, according to the study. “A readjustment of Germany’s Middle East policy … in favor of more intensive relations with producer countries such as Iran and Saudi Arabia, which have the largest conventional oil reserves in the region, might put a strain on German-Israeli relations, depending on the intensity of the policy change,” the authors write.

When contacted by SPIEGEL ONLINE, the Defense Ministry declined to comment on the study.

Oil Drum Translation of Leaked Document

Peak Oil

Implications Of Resource Scarcity On (National) Security

Center for German Army Transformation, Group for “Future Studies”

July 2010

1. Introduction

The focus of the document is on the topic of finite resources, using Peak Oil as an example. The report is part of a series of publications focused on the long term (30 years) with the intent to enable the Ministry of Defense to take action early.

In the past, resources have always triggered conflicts, mostly of regional nature. For the future, the authors expect this to become a global problem, as scarcity (mainly of crude oil) will affect everybody.

The authors confirm multiple views on Peak Oil timing and concede that there will be Peak Oil eventually. The study isn’t about positioning the problem on a timeline, but instead about the consequences of a peak. They expect major consequences with a delay of 15-30 years after the peak has hit.

The report refers to the uncertainty of reserve statements mainly in OPEC countries based on the quota allocation method within OPEC but also refers to the possibility of better extraction technologies.

They suggest that it has become urgent to understand those consequences of an eventual peak now in order to have enough time to adapt.

2. The Importance of Oil

2.1 Oil as a driver of globalization

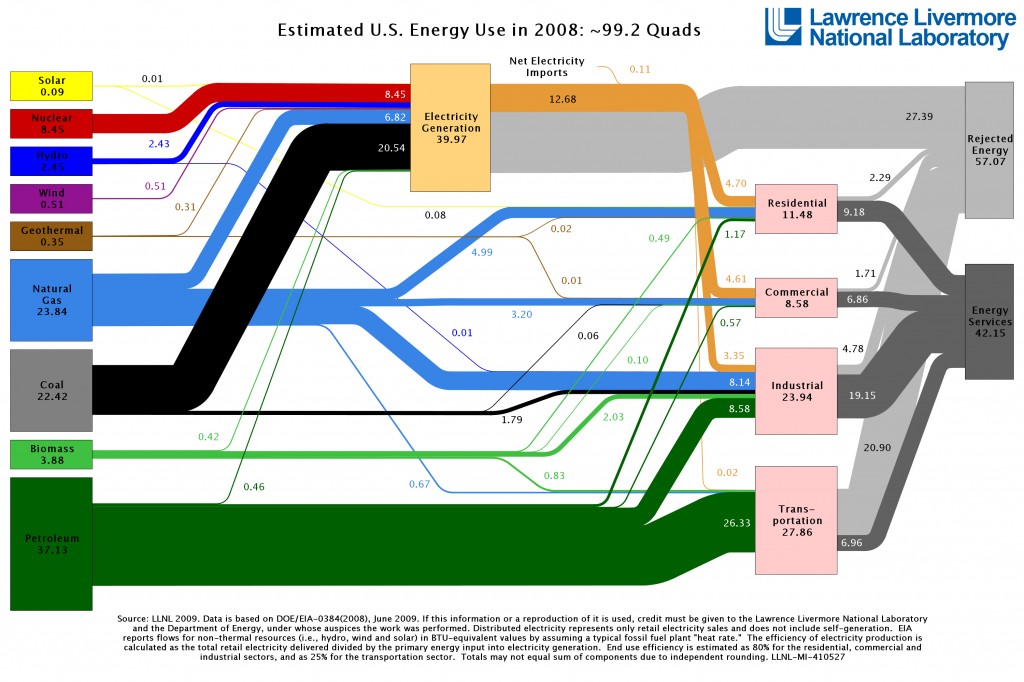

95% of all industrial outputs is dependent on oil as a fuel and/or as a chemical base for polymer production etc. Oil has become a key driver of modern lifestyle and globalization.

Substantial oil price increases poses a systemic risk, not just for obvious things like transportation, but equally for other subsystems.

Thus, internationally, but equally nationally, there is a vital interest in securing access to oil, which is currently possible on world spot markets, with OPEC being cooperative due to a mutual dependency between key actors (and a massive presence of the U.S military in the Gulf region).

Yet, on the other hand, regional conflicts can always at least partially be attributed to resources, such as in the Caucasus region, the Middle East or in Nigeria. They may also fuel conflicts due to the wealth they create (such as in Africa).

The report sees – within a timeframe until the year 2040 – a changed international security layout based on new risks (including transport risks for fuels) and new roles of actors in a possible conflict around the distribution of increasingly scarce resources.

2.2 German energy security

The term is defined narrowly as “reliable energy supply”, and then extended to include environmental objectives, technology transformation of societies, planning for energy demand and the long-term planning of a national strategy, tied in with international organizations.

This expansion of the view is seen as required based on the globalization of energy markets. However, the report then narrows in scope again to the possible risk from a supply shock, focusing on the key suppliers of oil: Russia, Norway and the U.K. It is noted that both European partners are already past their peak and that Germany is increasingly dependent on Russia, which currently is reliable but not necessarily so in the long term. Given the expected decline in German energy consumption, the Russian share will likely be 40% by 2025, with the Middle East, Africa and sources around the Caspian Sea making up for the increasing gap from declining European production.

3. Possible Scenarios After Global Peak Oil

This chapter looks at gradual changes (3.1.) and the risk of disruptive changes (3.2) past a certain tipping point.

3.1 General interdependencies driven by Peak Oil

3.1.1 Oil as a deciding factor in international relationships

With increasing scarcity, producers are increasingly in an advantageous position, both from high revenues and access to cheaper oil when compared to spot market prices. This partly reverses the trend to free oil markets which took place after the ’70s shocks, and gives those countries more control over the supply chain, with a risk of monopolies and nationalizations, and of “political pricing.”

Further, oil producers use increasing amounts of their production internally at lower prices, which increases domestic consumption and inefficiencies, accelerating the problem. [The authors miss out on the fact that high oil prices also bring more wealth to the country which AGAIN increases resource consumption].

The report then looks at increasing “strategic” moves by key actors including the Chinese CNPC (China National Petroleum Corporation), which tries to grab the sources that are still available (particularly in Asia and Africa), but often at relatively unattractive conditions.

Overall, the authors expect a reduction of “free market” mechanisms in oil trade, and a rise in more protectionism, exchange deals, and political alliances between suppliers and customers, which could lead to significant geopolitical shifts. Equally, the authors expect this interdependency to shape foreign affairs of oil importers, making them more tolerant towards rogue behavior of suppliers out of sheer need.

Overall, higher volatility and loss of trust are seen as possible outcomes in a world where oil supplies are limited, increasing the need for “oil related diplomacy” and thus increasing the risk of moral hazard among all actors, which in turn decreases overall global supply security.

The report then refers to already existing actions of the German government to tie close economic relationships with energy suppliers, and to the tendency of consuming countries to reduce oil dependency, trying to steer clear of risks of future supply shocks.

The Middle East is identified as a very dangerous region with high external involvement from many players and thus a very unstable overall situation.

Overall, the report expects a reduction of the importance of “Western values” related to democracy, and human rights in the context of politically motivated alliances, which increasingly are driven by emerging economies such as China – likely leading to double standards. Emerging economies are equally expected to receive higher recognition in international organizations, particularly those with strength in resources (such as Russia).

3.1.2 New security risks based on additional/alternative energy resources

New conflicts are potentially arising from oil exploration in international or disputed ocean waters, where multiple issues arise, particularly around the Arctic Circle, with further geopolitical risks for conflict.

Also, the shift to natural gas is reviewed as an extension of the “oil age”, because it might be able to replace crude oil as a bridging source until new solutions are found. The risks for problems from transporting gas (pipelines) and the related issues (as seen between Russia and its neighbors during the past years) are highlighted.

Equally, nuclear power as a potential source is highlighted – emphasizing the risk for safety and the proliferation of nuclear technology. This would also require an increasing shift towards electricity.

Equally, the competition between biofuel and food production is highlighted, showing the limits of biofuel outputs to compensate for reductions in oil availability, and also showing risks for water supply and soil degradation from excessive use.

Overall, the authors see a trend to increase the energy autonomy of entire regions from external supplies, both in the ability to generate alternative fuels (from biofuels and coal), but particularly in electricity generation.

3.1.3 A shift in roles between private and public actors

Based on the increasing importance of oil, governments are becoming more relevant in securing the benefits of oil, both on the supply and on the demand side. This puts a higher emphasis on political negotiations and deals, and increases the risks for nationalizations of resources and key exploration activities.

Exploration licenses are seen as a key area where bidding wars (including non-financial commitments) might emerge. Equally, increasing pressure to renegotiate or revoke already existing licenses might emerge. Ultimately, each country will try to secure sufficient oil to maintain its standard of living.

On the other hand, private enterprises are seen on the rise in protecting infrastructure and ensuring production and transportation security in less developed regions, particularly if weaker countries become unable to keep their own services up.

The dependency on oil-related infrastructure (pipelines, refineries, harbors, key pathways on oceans) will increase, and thus the risk. Damaging infrastructure through hostile acts (sabotage, war) might become an attractive target for groups or countries with a tendency to use violence. The same is expected for electricity and natural gas-related infrastructure – they all might require higher protection.

Generally, the focus of risks is expected in the region which the authors consider the “strategic ellipse” (a term used for the region East of Europe reaching from Saudi Arabia in the South to Russia and former Soviet Union countries in the North), because a majority of oil reserves are located in this area.

3.1.4 Economic and political crises as a consequence of the transition to “post-fossil” societies

A number of risks of higher oil prices are seen for modern economies, particularly in transportation. Security risks are seen in resulting systemic crises.

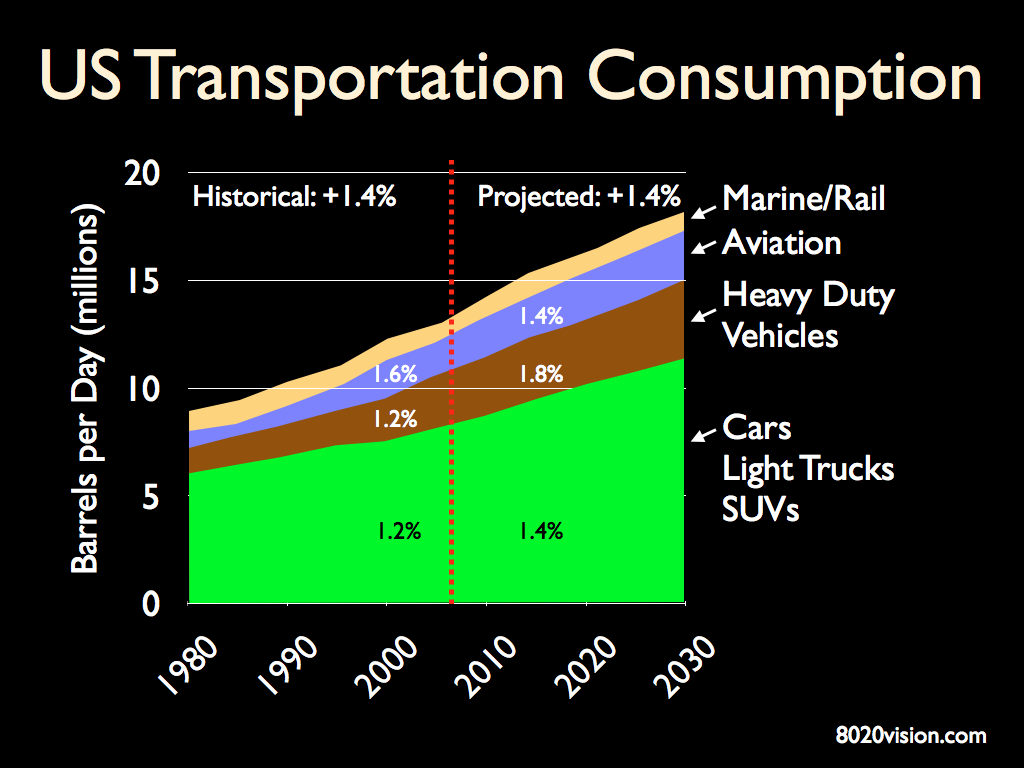

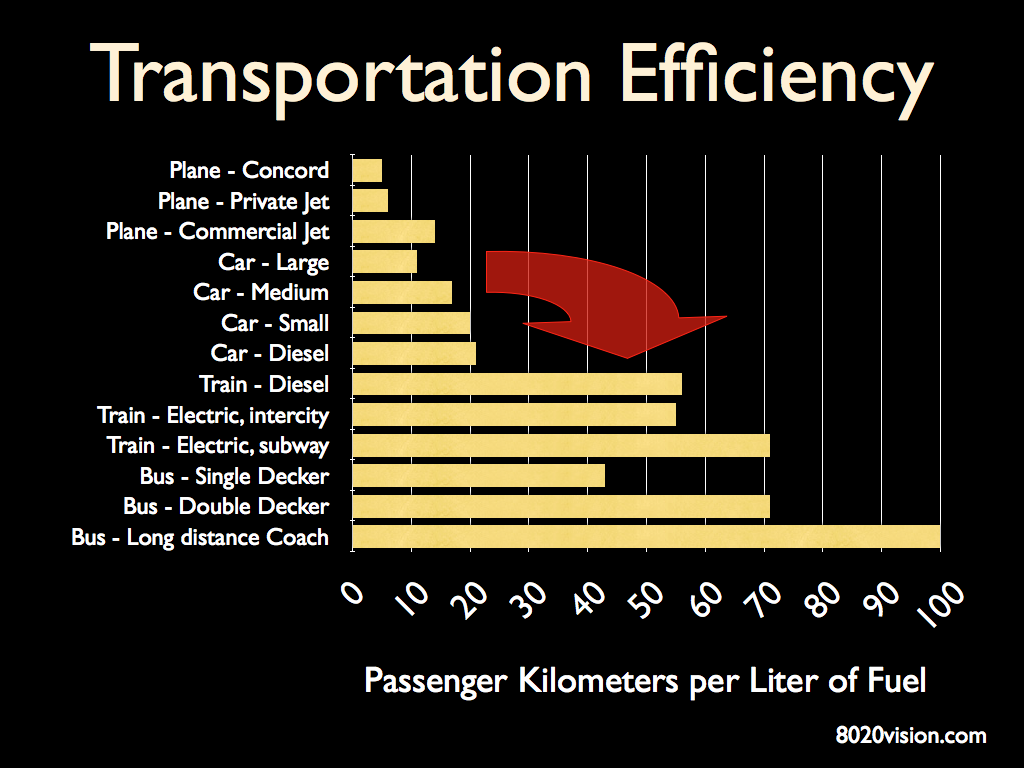

A first direct consequence of higher oil prices and lower availability of fossil fuels is a possible reduction in transportation capacity, equally in individual transportation and in freight forwarding. This might lead to another “mobility crisis” for societies that heavily depend on cars and trucks.

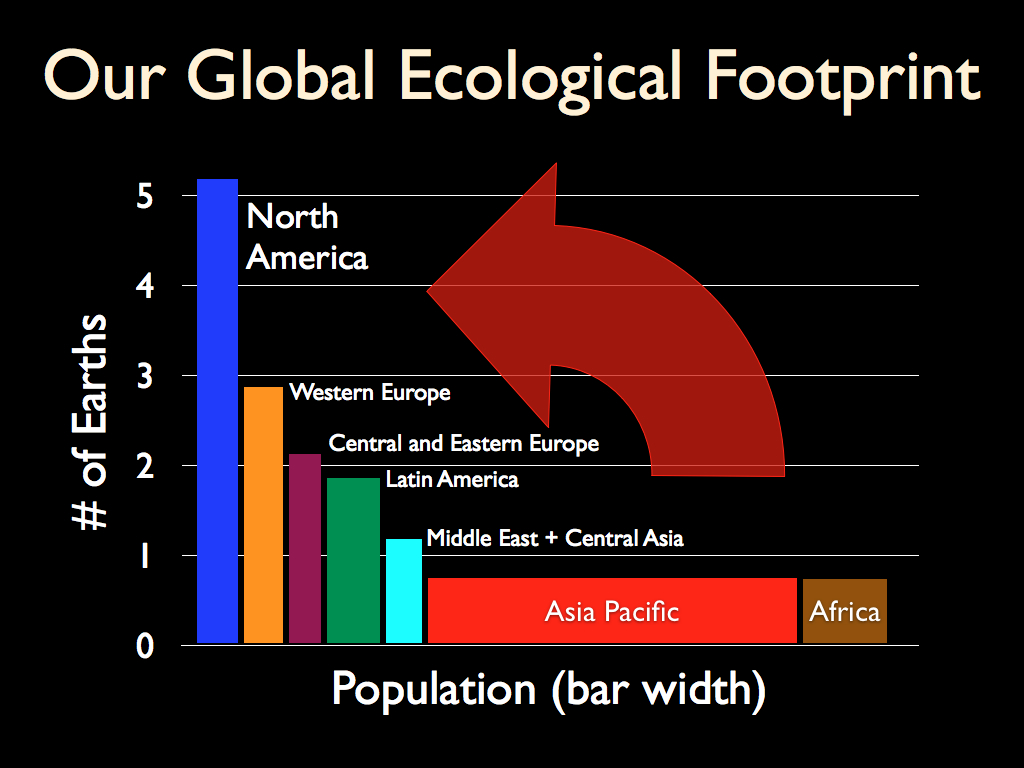

Higher cost in commercial transportation markets might severely affect current supply chains, and no alternatives are in sight (electric trucks don’t exist yet). Food particularly might become a critical issue for countries that are a) highly dependent on imports and b) are susceptible to price-increases of food products, particularly affecting Africa, parts of Asia and Latin America, and the Middle East.

High oil prices would further affect almost all aspects of society, as it will also influence the cost of chemicals and all products derived from them, which might substantially alter the nature of value chains and make certain things uneconomical – ultimately leading to higher unemployment during a transformational phase away from an oil based economy. This might particularly affect the German car industry.

Limits in availability might also strengthen regulatory efforts, encourage the allocation of energy (oil) by rationing schemes and possible other actions limiting free markets.

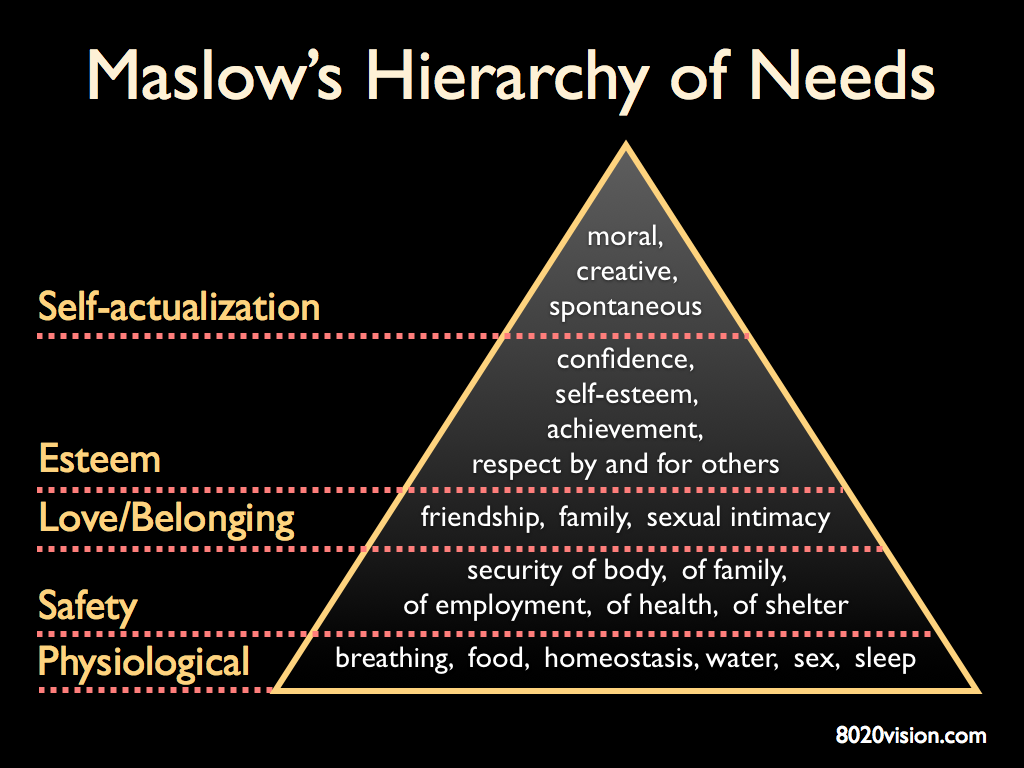

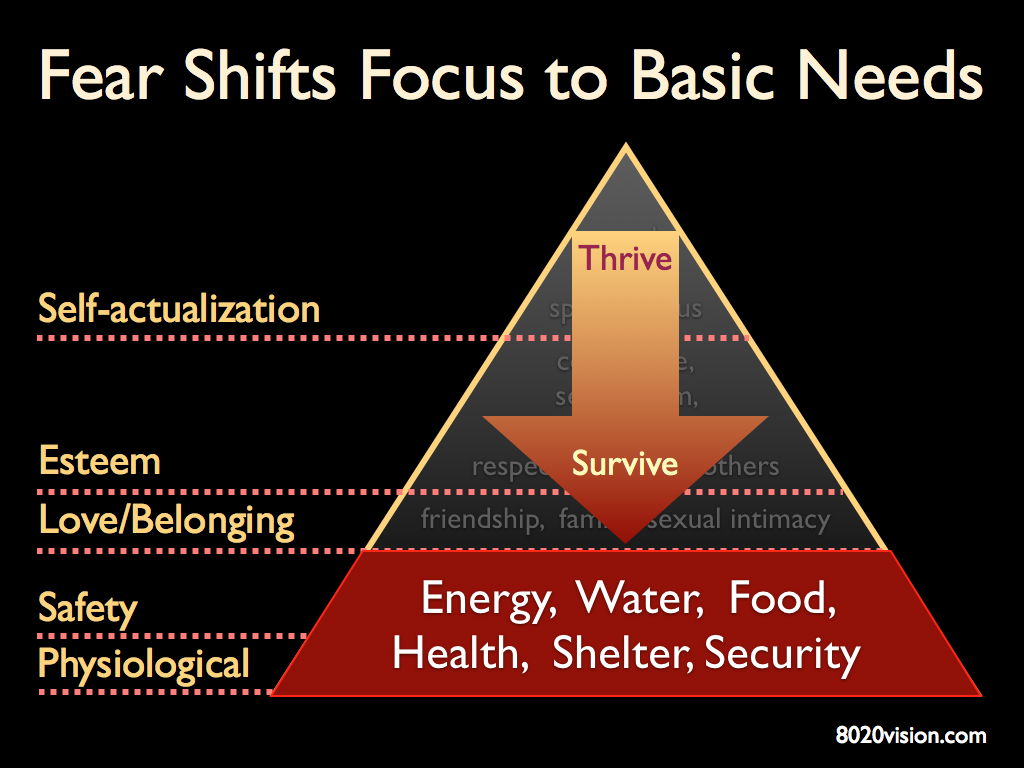

Additionally, the changes and likely reduction in standard of living might render societies less stable and make them more attracted to extremist political positions and even trigger changes in government systems, as trust into key actors in politics will diminish. This might be a particular risk for the relatively young democratic countries in Eastern Europe.

3.1.5 More selective intervention – key actors overwhelmed

Overall, more expensive transportation and increasing problems “at home” might reduce the ability of larger countries to intervene internationally (politically and/or with military action), and also lower the readiness to provide help to poorer countries. The focus will be more on a country’s (energy) interest for itself and not so much on an ideal of transferring Western values. The gap will likely not be filled by NGOs, as they will be affected by similar limits.

Overall, international institutions will be weakened, as they will have less resources to provide help and support, and it becomes equally possible that help will be attached to direct (energy) needs of the donors.

3.2 Systemic risks after reaching a “tipping point”

In addition to the gradual risks, there might be risks of non-linear events, where a reduction of economic output based on Peak Oil might affect market-driven economies in a way that they stop functioning altogether, leaving the possibility of a relatively steady downward trajectory.

Such a scenario could develop through an initially slow decline of trade and economic activity, combined with higher stress on government budgets from lower tax income, higher social cost and growing investment into alternative technologies.

Investment will decline and debt service will be challenged, leading to a crash in financial markets, accompanied by a loss of trust in currencies and a break-up of value and supply chains – because trade is no longer possible. This would in turn lead to the collapse of economies, mass unemployment, government defaults and infrastructure breakdowns, ultimately followed by famines and total system collapse.

4. Challenges for Germany

4.1 Risk of new dependencies for Germany

Oil as a new factor of global power would create significant dependencies for Germany, and in order to avoid supply issues, strong ties with suppliers are a must, but equally a diversification of supply relationships, taking into account that a supplier might intentionally reduce capacity to accomplish political objectives.

Among the key supplier countries is Russia (supplying 35% of German oil imports), where reliability risks are prevalent, given past experience. Natural gas, as a possible temporary substitute, bears the same risk (37% comes from Russia). Thus, a diversification becomes essential.

4.2 Focus of politics on supply relationships

Germany needs strong and reliable ties to Russia and other Caspian Sea countries. This might create some challenges in international relations, particularly with smaller Eastern European countries [like Poland]. Thus, intensifying relationships to the Middle East might be equally relevant. However, all those relationships have an inherent risk of being instruments in conflicts, which puts a certain limit on treating all foreign partners the same.

4.3 More pragmatic foreign policy

The need to mitigate supply risks might require some compromises on foreign affairs topics (such as human rights). Equally, more active diplomatic efforts will be required with a focus of energy security in mind. This is more difficult given Germany’s reluctance to engage in political power play due to its history, but needs to be tackled in order to deal with the challenges ahead. The authors don’t want to encourage military solutions, but suggest a strong preventive development of political and diplomatic initiatives to tackle the problem.

4.4 Importance and freedom of industrial nations reduced

All industrial nations that depend on energy imports will become more dependent on new partners, both in emerging economies and supplier countries. This requires a new focus in foreign affairs, sometimes giving up standards in negotiations with countries that have different cultures and political systems.

4.5 Help in stabilizing supplier countries at risk

Some supplier countries (and surrounding regions) might be destabilized by the force of higher resource prices. This is an area where Germany needs to help by providing support for nation building and conflict resolution on the national and international level. This is in conflict with the lower economic power likely to result from Peak Oil, which might make interventions less likely and requires new approaches of “stabilization with lower effort.”

4.6 Growing conflict potential concerning the Arctic Circle

Germany might have to take positions in case of an upcoming conflict regarding resources in the Arctic Circle, where multiple countries (including Russia) have open claims for accessing oil and gas fields. This requires further research.

4.7 Nuclear technology proliferation

The risk for nuclear technology proliferation and thus more countries with the potential for nuclear weapons (and the risk for terrorists having access to nuclear material) is growing due to the proliferation of nuclear technology for energy generation. Equally, risks for terrorist attacks and accidents on German soil are rising. Both scenarios require more surveillance, intelligence and preventive action.

4.8 Higher conflict potential regarding critical infrastructure

Energy delivery infrastructure for all sources including electricity will have a higher importance in an oil constrained world, thus, securing its reliability, security and availability becomes mission-critical. International cooperation is needed to secure large international supply paths (pipelines, sea routes).

4.9 Larger “energy regions” change international alliances

The expectation of stronger connections between suppliers and consumers across continents creates different settings for current international alliances and security risks. DESERTEC (a large power production system in Northern Africa based on CSP) would require different settings even for military strategies.

4.10 Peak Oil for armed forces

Armed forces would also be significantly affected by fossil fuel limits, as they are very dependent on oil products. Significant investments in alternative energy procurement technologies (biofuels, coal-to-liquids – Fischer-Tropsch) and applications (electric and hybrid vehicles) would be required, with long transition times. Further, local energy-independence of stationary troop infrastructure (like military bases) using more renewable sources would be beneficial. The long term objective would be to fully convert Germany’s armed forces to only use renewable energy sources by 2100.

4.11 Crude Oil as a systemic risk

For scenarios which end with a complete destabilization of societies, Germany is at a significant risk given its strong participation in a globalized economy. Being still able to act requires a number of basic infrastructures to keep functioning, both for the country and its armed forces. Work is required to look into redundancy, high-resilience of infrastructure and local self-organization approaches.

5. Summary

The report sees significant risks arising from an unavoidable peak in oil production, which go beyond gradual shifts in energy systems and economies. This will likely lead to economic change and new geopolitical risks that affect much more than just what we can anticipate. The overall ability to describe exact outcomes is very limited, as many scenarios are possible, and further research is required.

Overall, more emphasis needs to be put on understanding and shaping international relationships with respect to energy security, anticipating and integrating the ongoing shift to different players in a resource-constrained world.

In any case, Germany has to identify and implement alternatives to the current transportation technologies that require oil, and put a similar emphasis on avoiding other dependencies, for example concerning rare earths.

For armed forces, Peak Oil creates significant risks, both from a mobility standpoint as well as from dependencies on other societal services. Understanding those risks requires further analysis and likely a very different approach in the future.

In general, more preparation is required for society and the army to make sure that problems are recognized and solutions are actively implemented.