Veteran investigative reporter and Pulitzer Prize winner Hedrick Smith’s new work, Who Stole the American Dream?, steps back from the partisan fever of the 2012 campaign to explain how we got to where we are today — how America moved from an era of middle class prosperity and power, effective bipartisanship, and grass roots activism, to today’s polarized gridlock, unequal democracy and unequal economy that has unraveled the American Dream for millions of middle class families.

On 22 September 2012, Hedrick Smith spoke at the Parish Hall on Orcas Island, WA, as part of the Crossroads Lecture Series. He spoke for about an hour, followed by a 20 minute question and answer session. His book is available on Orcas Island at Darvill’s Bookstore (a signed copy), or at Amazon.

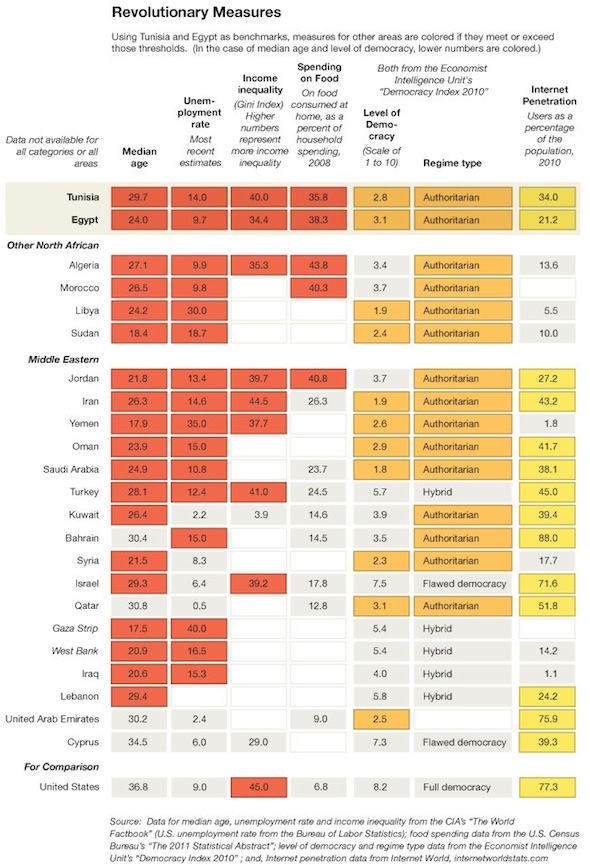

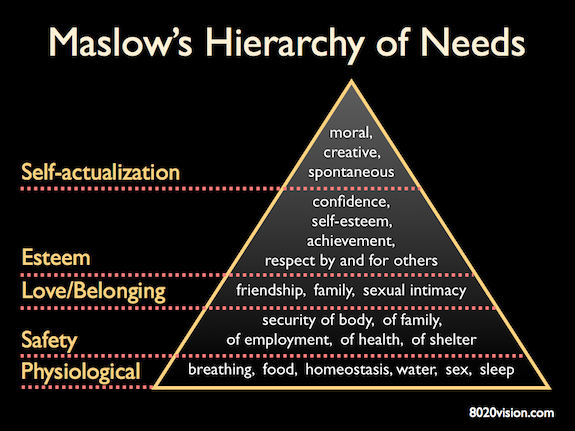

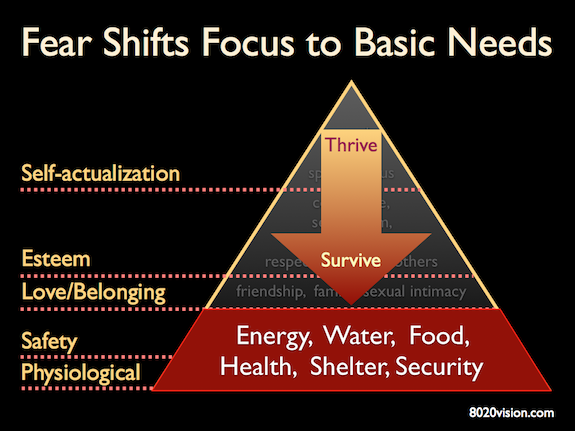

Smith’s book is brimming with fascinating insider stories that detail the shift from a strong middle class of the 50s and 60s, to the current weakened middle class, with an income inequality that is at an all time high, ranking with that of Rwanda and Uganda.

This didn’t happen by accident. Smith details how, beginning in the 1970s, corporate attorney Lewis Powell sparked a political rebellion with his call to arms for Corporate America. Like a gripping detective story, Smith follows the trail through to present day. Chronicling a stunning shift in power, away from a healthy growing middle-class, toward a superPACed, lobbyist fueled, special interest driven, well oiled, corporate powered, political machine.

Over the past decade, at the center of the machine, stands the “Gang of Six” and Washington insider Dirk Van Dongen, the man behind the curtain, who coordinates very effective lobbying of our elected officials. The Gang of Six include the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the Business Roundtable, the National Association of Manufacturers, the National Federation of Independent Business, the National Restaurant Association, and Van Dongen’s own National Association of Wholesaler-Distributors.

Who Stole the American Dream? makes for compelling reading, and at the end, Smith offers up a grassroots-centered strategy for reclaiming the dream – restoring balance to our economy and re-building a healthy middle-class. The video above will give you a summary understanding of what is well detailed in his book.

Corporate lobbyists funnel billions of dollars to our elected officials each year. Recent studies show that for every dollar spent lobbying, business receives over $220 back in legislation that favors the business.

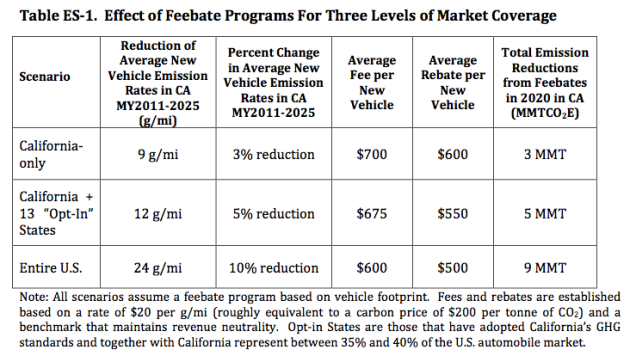

On climate change alone, 770 companies hired 2,340 lobbyists, up 300% in past 5 years. Most of those companies have vested interests in fossil fuels and benefit from delay of legislation that would speed the transition to clean energy.

In 2011 private companies and special interest groups spent $3.32 billion lobbying their agendas. In 2010, they spent even more at $3.54 billion. From 2008 to 2010, 30 Fortune 500 companies spent more money on lobbying than they did on taxes.

In an unusual moment of candor, here’s what Senator Dick Durbin had to say about corporate money and politicians:

“I think most Americans would be shocked, not surprised, but shocked if they knew how much time a United States Senator spends raising money.

And how much time we spend talking about raising money, and thinking about raising money, and planning to raise money.” Dick Durbin, 30 March 2012

Depending on status and influence, our elected officials in Congress typically raise about $5,000 to $30,000 per day. They spend a good part of each day dialing for dollars, asking businesses to send them money. It is against the law (the Hatch Act) to make those calls from government property, so they walk to call centers located conveniently just a few minutes from Capitol Hill.

Money in Politics

For more on how corporations and our elected officials are joined at the hip, see the excellent series on Money in Politics. Here’s an excerpt from that series:

So senators and congressmen go across the street to private rooms in nongovernmental buildings, where they make call after call, asking people for money.

In other words, most of our lawmakers are moonlighting as telemarketers.“If you walked in there, you would say, ‘Boy, this is the about the worst looking, most abusive looking call center situation I’ve seen in my life,'” says Rep. Peter Defazio, a Democrat from Oregon. “These people don’t have any workspace, the other person is virtually touching them.”

There are stacks of names in front of each lawmaker. They go through the list, making calls and asking people for money.

The fundraising never stops, because everyone needs money to run for re-election. In the House, the candidate with more money wins in 9 out of 10 races, according to the Center for Responsive Politics, a nonpartisan group that tracks money in politics. In the Senate, it’s 8 out of 10.

It’s not uncommon for congressmen to average three or four hours moonlighting as telemarketers. One lawmaker told me if it was the end of the quarter and he really needed to make his numbers, he’d be there all day long.

The fox is in the hen house. Time to get the big money out of politics. Surely our elected representatives don’t want to do this demeaning begging for money. Surely they would like to start making laws and setting public policy based on the merits of an issue. Right?

Recommended Reading

Who Stole the American Dream? by Hedrick Smith

When Does the Wealth of a Nation Hurt its Wellbeing? by Jay Kimball

Income Inequality: A Congressional Report Card by Jay Kimball

Money in Politics part of the NPR Planet Money series

Fair Elections Now Act is legislation to get big money out of Federal elections and replace it with grassroots public funding. More details here and here.