Keywords: growth, consumption, GDP, global economy, China, India, consumerism

Robert Reich wrote a thoughtful article on Why Growth is Good. Highlights of the article are below. In it, he differentiates between growth and consumption.

Growth is really about the capacity of a nation to produce everything that’s wanted and needed by its inhabitants. That includes better stewardship of the environment as well as improved public health and better schools.

A couple years ago I wrote an article – Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz on Sustainability and Growth – in which Stiglitz talked about the idea that “we grow what we measure.” Here’s an exerpt from the end of that article that I think is relevant to Reich’s article:

For me, what Stiglitz is getting at is: We grow what we measure (GDP), and because we are measuring the wrong stuff, we are growing wrong. It seems to be in our DNA to want to “grow,” but like a garden, don’t we have a choice about what we grow? Are there ways we can grow our economy that restore abundance rather than consume it? What are the essential things to measure so that we are growing good things?

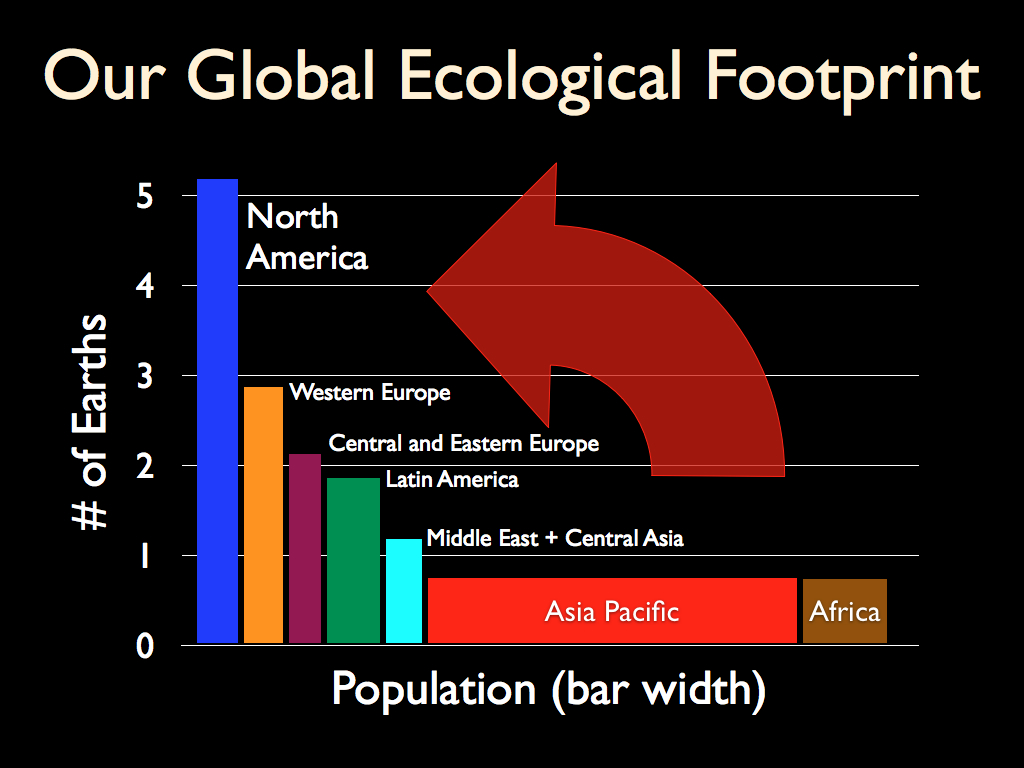

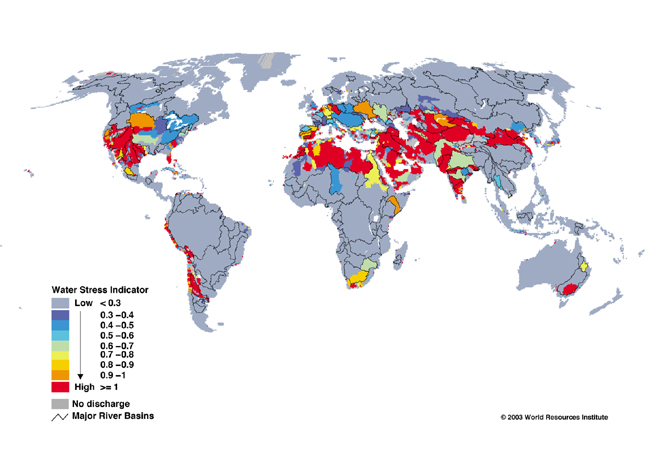

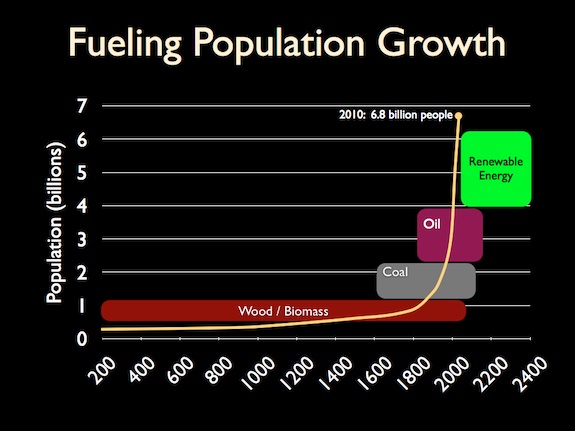

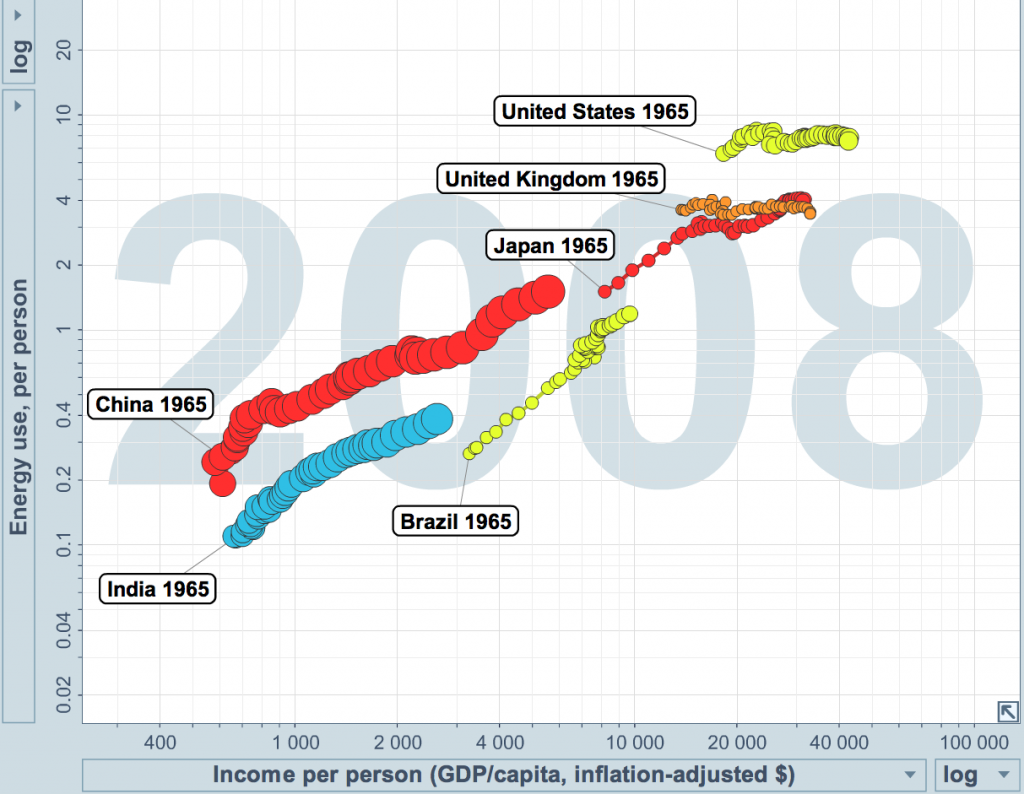

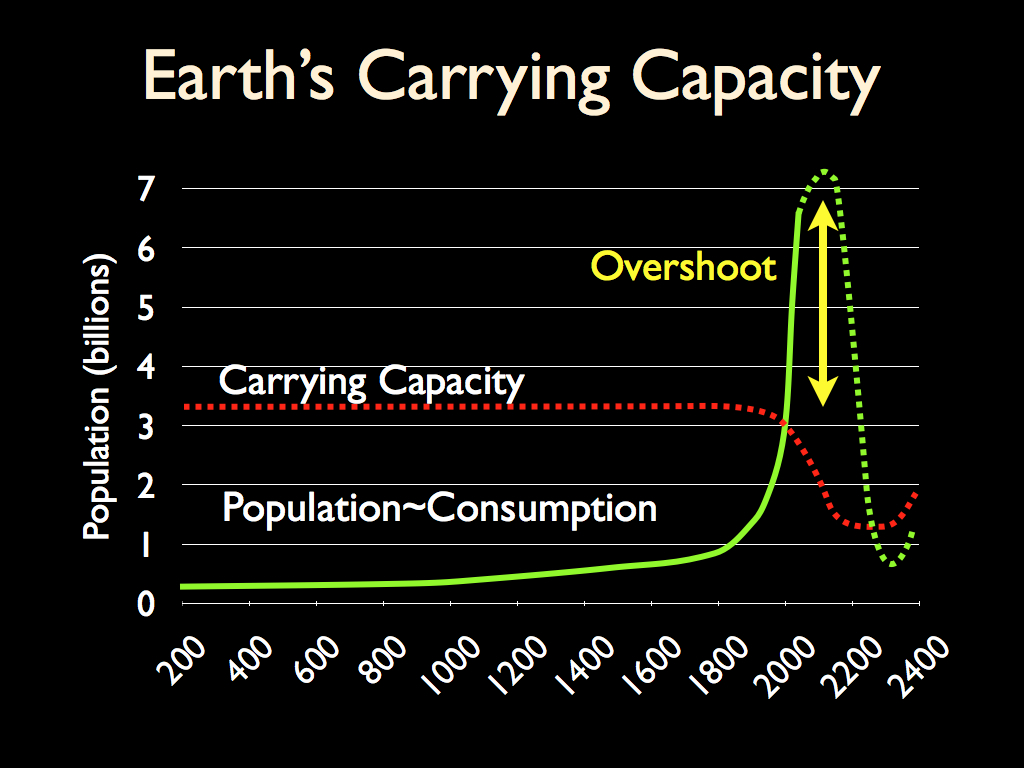

Using ecological footprint data from Global Footprint Network we can see the current state of consumption for North America and the rest of the world. American per capita consumption is legend. China and India are adopting their own versions of American-style consumerism. All nations are bumping up against the limits of the earth to provide what is needed for growth. We are collectively challenged to find new ways to grow, more lightly, in ways that restore rather than deplete.

N.B. The width of bar proportional to population in associated region. Ecological Footprint accounts estimate how many Earths were needed to meet the resource requirements of humanity for each year since 1961, when complete UN statistics became available. Resource demand (Ecological Footprint) for the world as a whole is the product of population times per capita consumption, and reflects both the level of consumption and the efficiency with which resources are turned into consumption products. Resource supply (biocapacity) varies each year with ecosystem management, agricultural practices (such as fertilizer use and irrigation), ecosystem degradation, and weather. This global assessment shows how the size of the human enterprise compared to the biosphere, and to what extent humanity is in ecological overshoot. Overshoot is possible in the short-term because humanity can liquidate its ecological capital rather than living off annual yields.

Highlights from Robert Reich’s Why Growth is Good

Economic growth is slowing in the United States. It’s also slowing in Japan, France, Britain, Italy, Spain, and Canada. It’s even slowing in China. And it’s likely to be slowing soon in Germany.

If governments keep hacking away at their budgets while consumers almost everywhere are becoming more cautious about spending, global demand will shrink to the point where a worldwide dip is inevitable.

You might ask yourself: So what? Why do we need more economic growth anyway? Aren’t we ruining the planet with all this growth — destroying forests, polluting oceans and rivers, and spewing carbon into the atmosphere at a rate that’s already causing climate chaos? Let’s just stop filling our homes with so much stuff.

The answer is economic growth isn’t just about more stuff. Growth is different from consumerism. Growth is really about the capacity of a nation to produce everything that’s wanted and needed by its inhabitants. That includes better stewardship of the environment as well as improved public health and better schools. (The Gross Domestic Product is a crude way of gauging this but it’s a guide. Nations with high and growing GDPs have more overall capacity; those with low or slowing GDPs have less.)

Poorer countries tend to be more polluted than richer ones because they don’t have the capacity both to keep their people fed and clothed and also to keep their land, air and water clean. Infant mortality is higher and life spans shorter because they don’t have enough to immunize against diseases, prevent them from spreading, and cure the sick.

In their quest for resources rich nations (and corporations) have too often devastated poor ones – destroying their forests, eroding their land, and fouling their water. This is intolerable, but it isn’t an indictment of growth itself. Growth doesn’t depend on plunder. Rich nations have the capacity to extract resources responsibly. That they don’t is a measure of their irresponsibility and the weakness of international law.

How a nation chooses to use its productive capacity – how it defines its needs and wants — is a different matter. As China becomes a richer nation it can devote more of its capacity to its environment and to its own consumers, for example.

The United States has the largest capacity in the world. But relative to other rich nations it chooses to devote a larger proportion of that capacity to consumer goods, health care, and the military. And it uses comparatively less to support people who are unemployed or destitute, pay for non-carbon fuels, keep people healthy, and provide aid to the rest of the world. Slower growth will mean even more competition among these goals.

Faster growth greases the way toward more equal opportunity and a wider distribution of gains. The wealthy more easily accept a smaller share of the gains because they can still come out ahead of where they were before. Simultaneously, the middle class more willingly pays taxes to support public improvements like a cleaner environment and stronger safety nets. It’s a virtuous cycle. We had one during the Great Prosperity the lasted from 1947 to the early 1970s.

Slower growth has the reverse effect. Because economic gains are small, the wealthy fight harder to maintain their share. The middle class, already burdened by high unemployment and flat or dropping wages, fights ever more furiously against any additional burdens, including tax increases to support public improvements. The poor are left worse off than before. It’s a vicious cycle. We’ve been in one most of the last thirty years.

No one should celebrate slow growth. If we’re entering into a period of even slower growth, the consequences could be worse.

For some excellent reading on this subject, check out the Recommended Reading section on Sustainable Business, Government, and Community. I especially found useful Lester Brown’s Plan B 4.0 and Jeffrey Sachs’ Common Wealth.