Roger Lowenstein, an outside director of the Sequoia Fund, and author of The End of Wall Street has an article in The New York Times called Paralyzed by Debt.

Highlights of the article are below. It is an excellent example of the impact uncertainty and consumer unease can have on consumer behavior. To put the article in context, here are a couple charts I use when talking about consumer behavior and impact on business and government economic models.

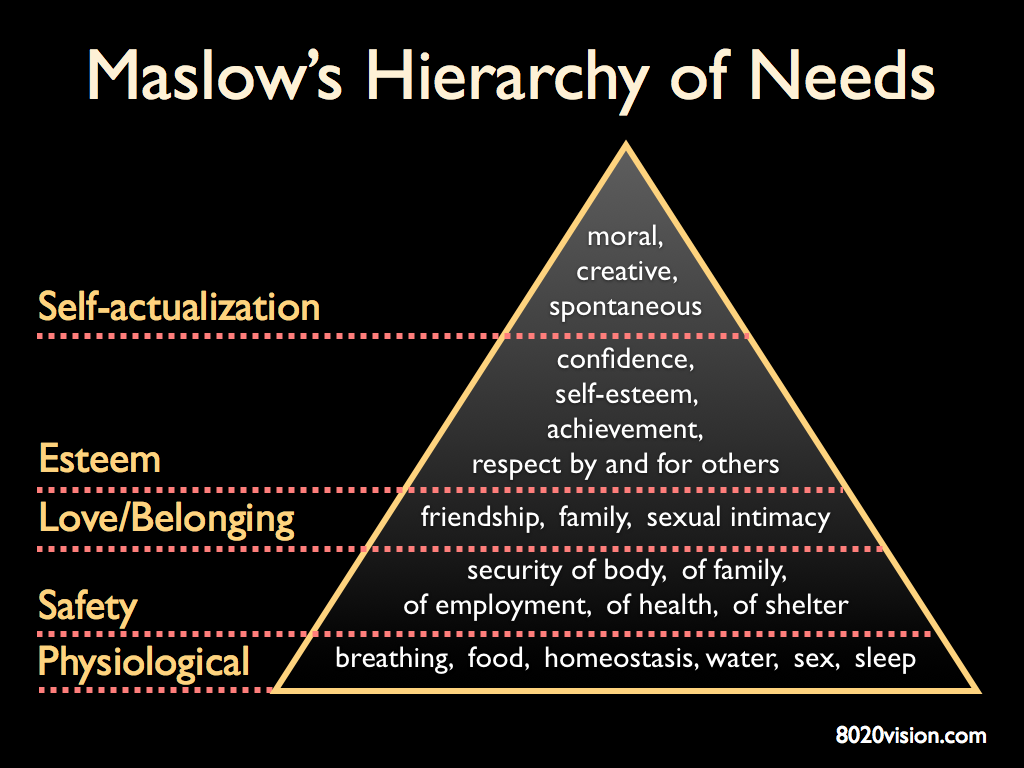

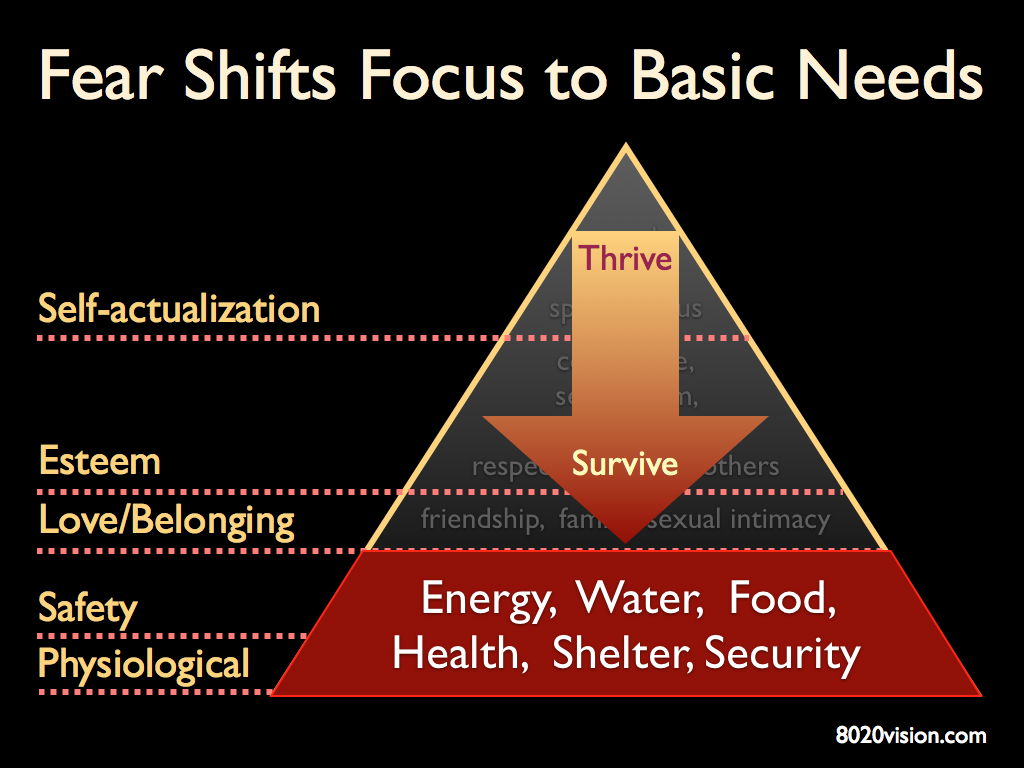

In Maslow’s hierarchy, the higher level needs can only be met when the foundational needs are solid. When something like the current recession, or high oil prices, or job insecurity occur, uncertainty rises and undermines our sense of wellbeing. We shift our focus to the basics – do we have a stable home situation, can we pay the mortgage, do we have a job, can we depend on it, can we afford healthcare, etc.? In short, the consumer mind shifts from Thrive to Survive.

We can see a practical example of this in the Personal Savings Rate. As the US entered the 2008 recession, the Personal Saving Rate, which has been trending down, did a stunning reversal in a single quarter, pivoting from .8 percent to almost 6 percent.

Lowenstein details how economic uncertainty impacted refinancing his home.

Highlights from NY Times Article: Paralyzed by Debt

Last month, my wife and I refinanced our mortgage. Though the rate was lower and we could have afforded more debt, we paid down a chunk of the balance. Don’t ask me why — it just felt better to owe less money. Time was, such thrift would have been hailed as patriotic. Now it threatens the economic recovery. Less borrowing means less to spend.

Suppose everybody did this? Well, it turns out, everybody has. Eschewing trips to the mall, Americans are paying off credit-card balances and home-equity lines. Despite low rates, mortgage demand has plummeted.

- 12.5% of household after-tax income is devoted to repaying debts (source: The Federal Reserve Board, 2010)

- Half of American workers have suffered a job loss or a cut in hours or wages over the past 30 months.

- The economy is Deleveraging. Credit in the economy is shrinking, as opposed to the normal state of affairs, in which, each quarter, people borrow more money and banks issue more loans.

Remarkably, this deleveraging has been going on for nearly two years. Ordinary Americans are behaving just as the banks they love to excoriate — having, formerly, assumed too much risk, they are going into hibernation. If credit, in the words of the writer James Grant, is money of the mind, people have become psychologically indisposed to minting it.

- Total household credit has contracted for seven straight quarters.

- Mortgage debt is down $462 billion from the peak, which it reached in November 2008.

- Bank-card borrowings, which peaked two months later, are off $126 billion.

- Auto loans have fallen $122 billion; home-equity lines, $77 billion.

As Stephanie Pomboy, publisher of the newsletter Macro Mavens, has pointed out, government transfers like stimulus spending and tax credits masked the effects of diminishing credit for a while. That is to say, even if people were unwilling to borrow, they were happy to spend money they got from the government. Now that government supports are being pulled away, the effects of deleveraging are in plain view. Home and car sales are plummeting again. Job growth has shrunk to a sliver. Personal bankruptcies are soaring. Deflation, a dangerous state of economic dead air, when prices fall from lack of demand, is a distinct possibility.

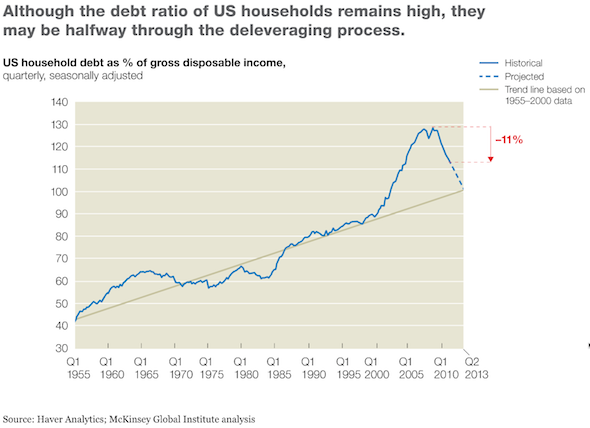

- In 2001, household debt reached a par with annual after-tax household income. (The average family owed what it earned.) By the peak of the bubble, in 2008, borrowings had surged to 36 percent more than income.

Which raises the issue: how much of that debt will have to be repaid before people return to their customary, and stimulative, profligacy? Thus far, we have undone only a portion of the excess. Household debt now stands at 26 percent more than income — still very high by historical standards. “There is no magical level where it should be,” says David Resler, an economist with Nomura Securities. “There is no clear equilibrium.”

- To return to the status quo of before the housing boom — say, back to debt to income ratios prevailing in 2000 — it would take five more years of deleveraging at the current rate.

McKinsey recently published an excellent review of the global deleveraging process that began in 2008. From their report:

Americans steadily increased their debt levels for a good six decades, but it wasn’t until the turn of the millennium that the ratio of household debt to income really soared. Yet by the second quarter of 2011, three years after the start of the global economic crisis, the US ratio had fallen 11 percent from its peak. At the current rate of deleveraging, it would return to trend as of mid-2013—a conclusion buttressed by a comparison between US households today and those of Sweden and Finland during the 1990s, when the two Scandinavian countries endured similar banking crises, recessions, and deleveraging episodes. In both, the ratio of household debt to income fell by roughly 30 percent from its peak. As the exhibit below shows, the United States has been closely tracking the Swedish experience, while households in Spain and the United Kingdom have only just begun to deleverage. To learn more, read “Working out of debt” (January 2012).

jaykimball says:

McKinsey has a good analysis of deleveraging. See: https://www.mckinseyquarterly.com/Economic_Studies/Country_Reports/Working_out_of_debt_2914

Alvarson Castrillon says:

Warm greeting! Insightful and in-depth issue.Hereby,I acknowledge and thank 8020 Vision for aharing so meaningful Stuff.Best regards! Alvarson

jaykimball says:

Thanks Alvarson!