The world’s farmers need a pay rise – or, come the mid-century, the other 8 billion of us may well find we do not have enough to eat.

True, this assertion flies in the face of half a century of agricultural economics orthodoxy – but please bear with me as I explain.

Globally and especially in developed countries, food has become too cheap. This is having a wide range of unfortunate – and potentially dangerous – effects which include:

- Negative economic signals to farmers everywhere, telling them not to grow more food

- Increasing degradation of the world’s agricultural resource base

- A downturn in the global rate of agricultural productivity gains

- An ‘investment gap’ which is militating against the adoption by farmers of modern sustainable farming and other new technologies

- A deterrent to external investment because agriculture is less profitable than alternatives.

- The decline and extinction of many local food-producing industries worldwide

- A disincentive to young people (and young scientists) to work in agriculture.

- Loss of agricultural skills, rural community dislocation and increased rural and urban poverty affecting tens of millions

- Reduced national and international investment in agricultural research and extension

- Lack of investment in water, roads, storage and other essential rural infrastructure

- The waste of up to half of the food which is now produced

- A pandemic of obesity and degenerative disease that sickens and kills up to half of consumers of the ‘modern diet’, resulting in

- Soaring health costs causing the largest budget item blowout in all western democracies

- The failure of many developing countries to lay the essential foundation for economic development – a secure food and agriculture base – imposing direct and indirect costs on the rest of the world through poverty, war and refugeeism.

From this list it can be seen that low farm incomes have far wider consequences for humanity in general than is commonly supposed.

Indeed, in a context in which all of the basic resources for food production are likely to become much scarcer, it may be argued that, indirectly, they imperil every one of us.

A Market Failure

This aspect of future global food security is primarily about a market failure.

At its ‘How to Feed the World’ meeting in October 2009 the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation stated that investment of the order of $83 billion a year was needed in the developing world alone, to meet the requirement for a 70 per cent increase in food production by 2050. (source: ii) However, almost in the same breath, it noted “Farmers and prospective farmers will invest in agriculture only if their investments are profitable.” (My emphasis).

The logic is unassailable. Today most of the world’s farmers have little incentive to invest in agriculture because the returns are so low. This applies as much to farmers in developed countries , as it does to smallholders in Asia or Africa.

Reasons for the low returns are not hard to find: farmers are weak sellers, trapped between muscular globalised food firms who drive down the price of their produce, and muscular industrial firms who drive up the cost of their inputs. This pincer movement not only discourages ‘developed’ agriculture but also prevents undeveloped agriculture from developing.

Nothing new here, you may say. So what has changed? The growing imbalance in power between farmers and those who dominate the food supply chain is what has changed.

Two decades ago most farm produce was largely sourced from local farmers by local buyers for local markets and consumers, as it was through all of history. In the 21st century there has been a massive concentration of market power in the hands of a tiny number of food corporations and supermarkets sourcing food worldwide. These are – quite naturally – doing all they can to reduce their input costs (farm prices) as they compete with one another. This is not a rant about globalisation: it’s a simple observation about one of the facts of global economic life.

The power of the farmer to resist downward price pressure has not increased. Indeed it has weakened, as the average producer now competes against some struggling farmer in a far away country, rich or poor, who is also simply trying to survive by selling at the lowest price.

The power of the global input suppliers – of fuel, machinery, fertilizer, chemicals, seeds and other farm requirements, has also grown as they concentrate and globalise. This makes it easier for them to raise the cost of their products than it is for farmers to obtain more for their wheat, rice, livestock or vegetables or to withstand input price hikes.

As a consequence of this growing market failure, the economic signal now reaching most of the world’s farmers from the market is “don’t grow more food”.

Its effect is apparent in the fact that world food output is now increasing at only about half the rate necessary to meet rising global demand, and that yield gains for major crops have stagnated.

While some will argue such cost/price pressures make for greater economic ‘efficiency’, the logical outcome of unrestrained global market power will eventually displace around 1.5 billion smallholders out of agriculture, with devastating consequences for the landscapes they manage and the societies most affected. Putting one in five of the Earth’s citizens out of work and destroying the food base is not a strategy any intelligent policy or government would advocate, one hopes. But it is one of those ‘externalities’ which classical economics sometimes omits to factor in – and is happening, nevertheless.

Global Degradation

In a recent satellite survey, researchers working for FAO reported 24 per cent of the Earth’s land surface was seriously degraded – compared with 15 per cent estimated by an on-ground survey in 1990. The FAO team noted that degradation was continuing at a rate of around 1 per cent a year. (source: iii)

Every agronomist and agricultural economist knows that, when farmers are under the economic hammer, a good many of them will overstock and overcrop in a desperate effort to escape the poverty trap leading to severe resource degradation. In drier, more marginal country, cost/price pressures can devour landscapes – and this is undoubtedly a major factor (though not the only one) in the degradation of land and water worldwide, especially in the world’s rangelands.

If we continue to sacrifice one per cent of the world’s productive land every year, there is going to be very little left on which to double food production by the mid-century: crop yields in 2060 would have to increase by 300 per cent or so universally, which is clearly a tall order.

Much the same applies to irrigation: “In order to double food production we need to double the water volume we use in agriculture, and there are serious doubts about whether there is enough water available to do this,” is how Dr Colin Chartres, director general of the International Water Management Institute summed it up recently. (source: iv) Dr Chartres estimates that doubling world food output could require up to 6000 cubic kilometres more water.

Solutions to land and water degradation are reasonably well known, and have been shown to work in many environments – but are not being adopted at anything like the rates necessary to double world food production or even to conserve the existing resource base. One reason is that farmers, in the main, cannot afford to implement them, even though many would like to do so. The economic signal is wrong.

As a result, world agriculture is today primarily a mining activity. We all know what happens to mines when the ore runs out.

Productivity Decline

There is also persuasive evidence that world agriculture is dropping off the pace – that it is no longer making the yield advances and total productivity gains achieved in the previous generation. In a recent paper Alston and Pardey (source: v) documented this decline both in the US and globally, attributing it significantly to falling investment worldwide in agricultural science and technology and extension of new knowledge to farmers.

The role of low returns in discouraging farmers, in both developed and developing countries, from adopting more productive and sustainable farming systems cannot be ignored. While a few highly efficient and profitable producers continue to make advances, the bulk of the world’s farmers are being left behind. Since small farmers feed more than half the world, this is a matter for concern.

One of the indirect effects of the negative economic signal for agriculture can be seen in the growing reluctance of governments to invest in agricultural research and development, and their increasing tendency to cut ‘public good’ research. This has happened in most developed countries and even in places such as China the level of ag R&D support is falling as a proportion of the total science investment. With agricultural R&D comprising a mere 1.8 cents of the developed world’s science dollar in 2000, one has a very clear idea how unimportant most of the world’s governments now consider food production to be. (source: vi)

The fact that agriculture appears perennially unprofitable and suffers from continuing social malaise probably contributes, subliminally, to a view among urban politicians that society ought not to be wasting its money funding research for such a troubled sector: there are a thousand other more attractive and exciting fields for scientific investment. This negative (and false) image of agriculture is an unspoken driver behind the reduced global R&D effort.

Today the world invests around $40 billion a year in agricultural research – and $1500 billion a year in weapons, as if killing one another were forty times more important than eating.

Is food too cheap?

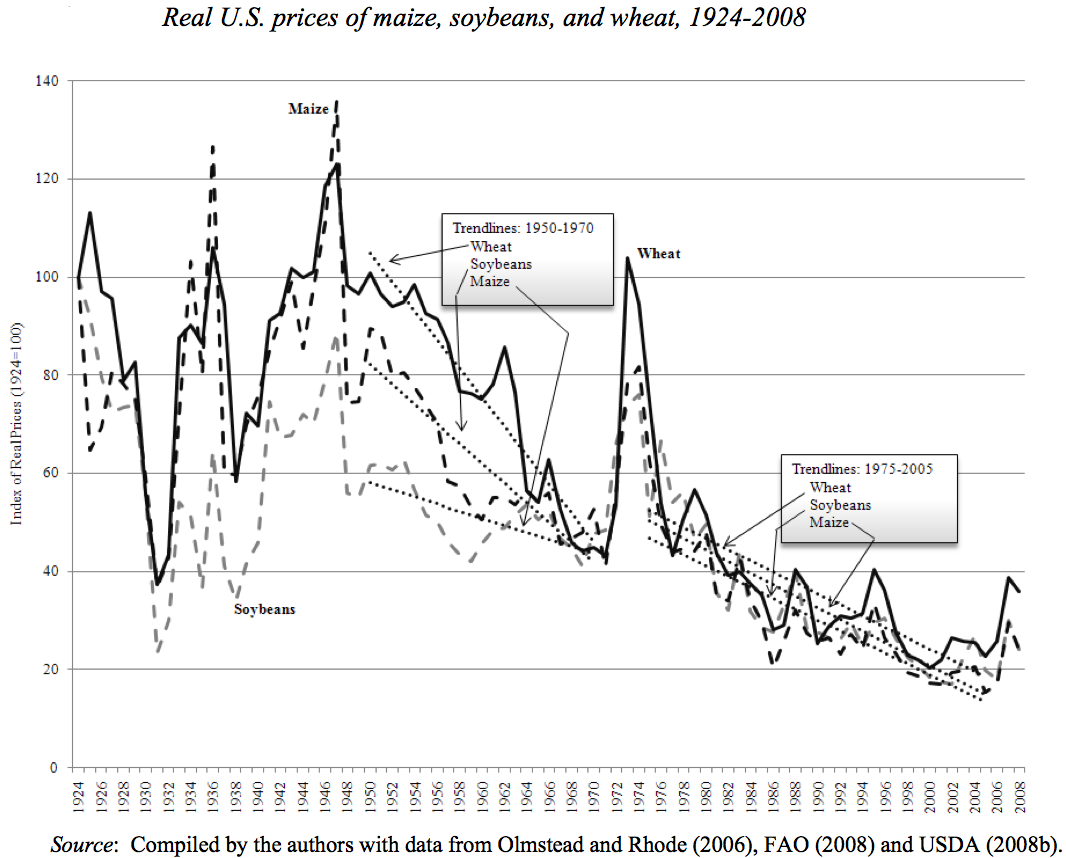

For affluent societies at least, food is now the cheapest in real terms it has ever been in human history.

Back in our grandparents’ time, in the early part of the 20th century, the average western wage earner devoted about a third of their weekly income to food. Rent was relatively cheap, people didn’t have cars, iPhone bills, plasma TVs, facelifts or overseas vacations – and food was essential. By the 1970s the amount of household disposable income spent on food was down to 20 per cent. Today it is around 11-12 per cent in Australia and similar in other western nations. As incomes rise in China and India, the proportion is falling there too.

When something is too cheap, people do not value it as they should. This produces a lack of respect for the product itself, for the people and industries involved in its production – farmers and scientists – and for the places it is produced and for the resources of land, water and human skills that produce it. This is one explanation for the negative image held by governments, businesses and most societies towards agriculture and its investment needs.

In an age where 3.5 billion humans have only the dimmest notion where their food comes from, lack of respect for the main thing that keeps them alive is coming to be a predominant ‘value’ in the human race and this is a potential danger.

A Culture of Waste

Food is now so cheap that developed societies such as the US, Britain and Australia throw away nearly half, while developing countries lose nearly half post-harvest. (source: vii)

Societies that pay their farmers such low returns, have found they can afford to send nearly half of the farmers’ efforts to landfill. Or burn in an recreational vehicle enough grain as biofuel in one week to feed a poor person for a year.

Where our ancestors stored, conserved and recycled nutrients, humanity now appears to waste 70% -90% of all the nutrients used to produce food. On farm, up to half the applied fertiliser does not feed crop or pasture but escapes into the environment. Of the harvested nutrients, some are lost post-harvest, in transport, processing and cooking – but more than 30 per cent are simply discarded, in the shops and in the home. Then we dump around 90 per cent of our sewage nutrients in the ocean.

In short, the modern food system has established a culture of absolute and utter waste, sustained only by the mining of energy and nutrients (from rock or soil), which will eventually run out or become unaffordable to most farmers.

The universal practice of recycling, in use since agriculture began more than 6000 years ago, has broken down. The planetary nutrient cycle is now at risk from the colossal nutrient pollution now occurring.

This situation cannot persist more than a few decades. We will need to recycle and invest in new systems – but for that to occur, farm incomes and the incentive to invest in food production must rise and the economic signal to invest in agriculture must change.

An Unhealthy Situation

Cheap food is at the root of a pandemic of disease and death larger in the developed world than any other single cause of human mortality, and spreading like wildfire in the newly-industrialised world. Cheap, abundant processed food is a driver for obesity, which now affects one in five humans, and plays a significant role in the society-wide increase in cancers, heart disease, diabetes, stroke and bowel disorders.

Cheap food, in other words, is an economic invitation to consumers – including millions of children – to kill themselves prematurely through overindulgence.

Cheap food is the chief economic driver of the greatest budget blow-out in all western democracies: healthcare.

Solving the Food Challenge

The purpose of this essay is to call attention to the effect a never-ending reduction in farmers’ incomes will have on world food security at a time of rising physical constraints to production, including scarcities of land, water, energy, nutrients, technology, fish and stable climates.

At the very time when most experts agree we should be seeking ways to double food output sustainably over the coming half-century, the ruling economic signal is: “don’t do it”.

Of course, we can simply obey the economic signal and allow agricultural shortfalls to occur – but that will expose 8 or 10 billion consumers to massive unheralded price spikes, of the sort experienced in 2008, which have a dire impact on the poor, start wars and topple governments – and will not benefit farmers as much as a stable, steady increase in their incomes.

Most of the world’s poorest people are farmers, and it follows that one of the most effective remedies for world poverty is to increase the returns to agriculture. True, this will involve raising food prices for the urban poor but they are less numerous and can more easily be assisted by other government measures. At present rural poverty is maintained throughout the world largely by the economic policy of providing affluent city consumers with cheap food.

It is necessary to state this essay does not advocate a return to agrarian socialism, protectionism, commodity cartels or an end to free markets. In fact, we probably need to move much faster and further towards totally free trade in agricultural products in order to encourage efficient producers – large and small – around the world.

But it does hold up a warning flag about the universal dangers of underinvestment, negative signals and sentiment, resource destruction and rural dislocation caused by the undervaluing of the one commodity humanity absolutely cannot do without, as we approach the greatest demand for food in all of history.

There are numerous ways this issue might be addressed. Here are a few:

- Price: through an educated “community consensus” that results in willingness on the part of consumers, supermarkets and food processors to pay more for food so as to protect the resource base and enable farmers to invest in new technologies (source: viii)

- Subsidy: by the payment of a social wage to farmers by governments for their stewardship on behalf of society of soil, water, atmosphere and biodiversity, separate from their commercial food production

- Regulation: by limiting by law those practices or technologies which degrade the food resource base and rewarding by grant those which improve it

- Taxation: by levying a resource tax on all food which reflects its true cost to the environment to produce, and by reinvesting the proceeds in more sustainable farming systems, R&D, rural adjustment and enhanced resource management.

- Market solutions: by establishing markets for key farm resources (eg carbon or water) that result in higher returns for farmers from wise and sustainable use.

- Public education about how to eat more sustainably; industry education about sustainability standards and techniques.

- A combination of several of the above measures.

The technical solutions to most of the world’s food problems are well-known and well understood – but they are not being implemented as widely as they should because of a market failure which prevents their adoption. To avoid grave consequences, affecting billions of people, this failure needs correction.

It also needs correcting because, as long as world food production remains an undervalued activity, then so too will investing in the research essential to overcome future shortages –crop yields, water use, landscape sustainability, alternative energy, the recycling of nutrients and the reduction of post-harvest losses. To satisfy a doubling in demand for food over the coming half century calls for at least $160 billion in worldwide agricultural R&D activity a year – equal to a tenth of the global weapons budget. However this would leave the world both more peaceful – and better fed.

It is not the purpose of this essay to solve the issue of how to deliver fairer incomes to farmers worldwide, but rather to foster debate among thoughtful farmers, policymakers and researchers about how we should go about it.

However it does question whether some of the ‘old truths’ of the 20th century still apply in the 21st, or whether the era of globalisation and resource scarcity has changed the ground rules.

It also asks whether the unstinted application of overwhelming market force against farmers is the act of a sapient species – or a mob of lemmings?

Over to the sapient ones among you.

–– Julian Cribb FTSE

Julian Cribb is Founding Editor of Science Alert, and is the principal of Julian Cribb & Associates, specialists in science communication. He is a fellow of the Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering.

Sources

i. Sources for this essay are those cited in Julian Cribb's book The Coming Famine, University of California Press, 2010. Since they take up 24 pages, we have not reproduced them all here. See the book at Amazon or UC Press for full reference listing.

ii. FAO High Level Export Forum, How to feed the World: Investment, Rome, October 2009. http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/wsfs/docs/Issues_papers/

HLEF2050_Investment.pdfiii. Bai ZG, Dent DL, Olsson L and Schaepman ME 2008. Global assessment of land degradation and improvement 1: identification by remote sensing. Report 2008/01, FAO/ISRIC – Rome/Wageningen

iv. Chartres C, World Congress of Soil Science, Brisbane, August 2010

v. J. Alston, J.M.Beddow, P. Pardey, “Mendel versus Malthus: research, productivity and food prices in the long run,” University of Minnesota, 2009. http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/53400/2/SP-IP-09-01.pdf

vi. Pardey P et al, Science, Technology and Skills, CGIAR report, October 2007.

vii. See for example Lundqvist, J., C. de Fraiture and D. Molden. Saving Water: From Field to Fork – Curbing Losses and Wastage in the Food Chain. SIWI Policy Brief. SIWI, 2008.

viii. In case this should raise a sceptical eyebrow, the recent stakeholder report by Woolworths Australia “Future of Food”, 2010, suggests at least some of the major players in the food game have a dawning grasp of the consequences of their actions and are now looking to invest in (mainly non-income) ways to support farmers.

For more on the global food issue, see:

Climate Change May Reduce Protein in Crops

Warmer Temperatures in China to Reduce Crop Yields