Charles M. Blow, one of my favorite “number crunchers”, and op-ed columnist at the NY Times, has a good article today on what causes a revolution. He turns the lens on Egypt and Tunisia, as well as other countries that might be poised for revolution, and looks at what factors can contribute to people rising up and overthrowing their government.

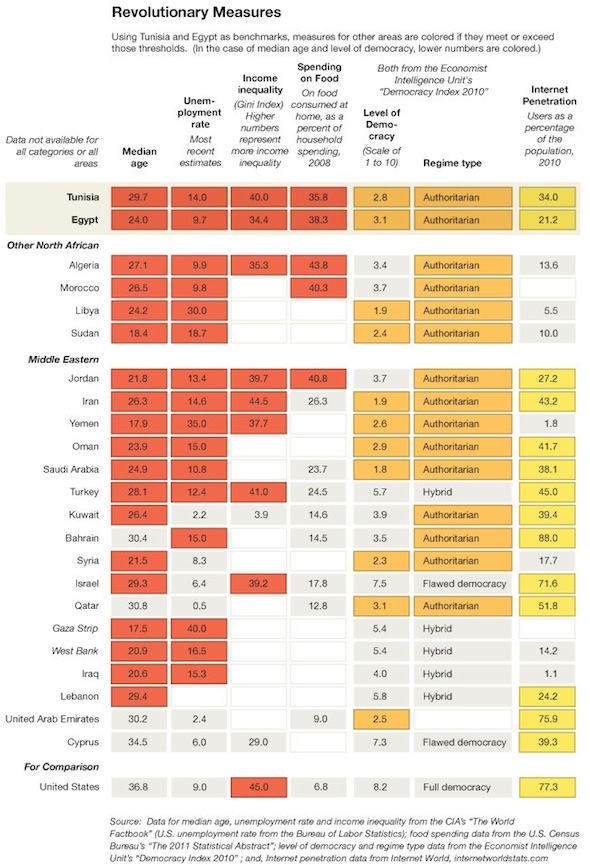

Though agitating factors like unemployment and age have featured in many articles on the situation in Egypt and Tunisia, Charles M. Blow digs deeper. He prepared the table below, which shows median age, unemployment rate, income inequality, food as a percentage household spending, level of democracy, regime type, and internet penetration.

Worth noting: The real US unemployment rate is about 16%, when considering the more comprehensive U6 Rate. The US has the highest income inequality of all the countries considered in the list above. The US ranks with Rwanda and Uganda. For more on that, see the recent 8020 Vision article When Does the Wealth of a Nation Hurt its Wellbeing?

Worth noting: The real US unemployment rate is about 16%, when considering the more comprehensive U6 Rate. The US has the highest income inequality of all the countries considered in the list above. The US ranks with Rwanda and Uganda. For more on that, see the recent 8020 Vision article When Does the Wealth of a Nation Hurt its Wellbeing?

I am glad Blow listed food as one of the metrics to consider. There is a proverb that governments ignore at their peril:

“Lo que separa la civilización de la anarquía son solo siete comidas.”

(Civilization and anarchy are only seven meals apart.)—Spanish proverb

Though Egypt is not unique – corrupt repressive governance and cronyism can be found at the heart of many dysfunctional nations – once corruption interferes with meeting the basic needs of the populace, revolution is imminent.

The Basics Of Revolution

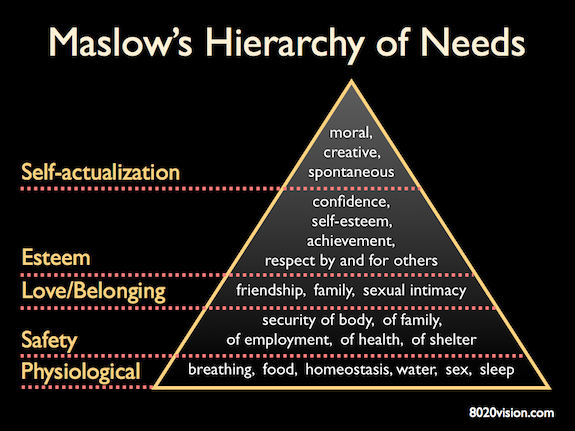

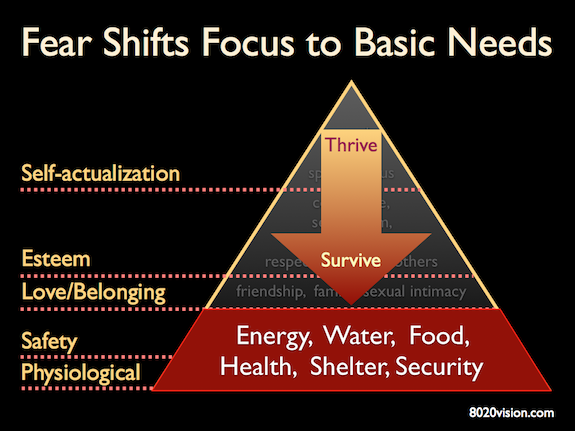

When I work with clients and this subject comes up, I like to turn to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs to put this in perspective. As we can see, two of Charles Blow’s metrics – food and unemployment – are fundamental components of basic human needs.

The lower down on Maslow’s pyramid a dysfunctional regime effects the populace, the deeper the impact, and the more likely the effected people will rebel. In other words, when a government fails to meet the basic human needs of its people, the people rise up.

Looking back in history for examples of how food and government are connected at the hip, our eyes come to rest on the Roman empire. Though the causes of the fall of Rome are debated still, one thing is certain: As the Roman empire devolved into the late-stage “Bread and Circuses” phase, once the farm system failed and the bread ran out, the rulers quickly lost the support of the people. The party was over.

The party is over in Egypt. President Mubarak now requires plainclothes thugs with clubs to beat back the public, losing what little credibility and dignity he might have had. How will he sleep? I don’t think the prideful Mubarak’s $60 billion family bank account will numb the shame he must feel as he watches the Egyptian army protect the people from his secret police.

As Tunisia and Egypt fail, Charles M. Blow scans his table of cold hard data and asks “Who’s next?”

“Seen through that prism (of food, income inequality, and internet penetration), Tunisia and Egypt look a lot alike, and Algeria, Iran, Jordan, Morocco and Yemen look ominously similar.“

A Global Perspective on Food

Pulling the lens back for a more global view – as world population expands inexorably – we are approaching a tipping point with regard to food production.

This week, a report that gained little attention in the news, but has major ramifications for every nation – especially those where food is a larger percentage of household income – was published by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

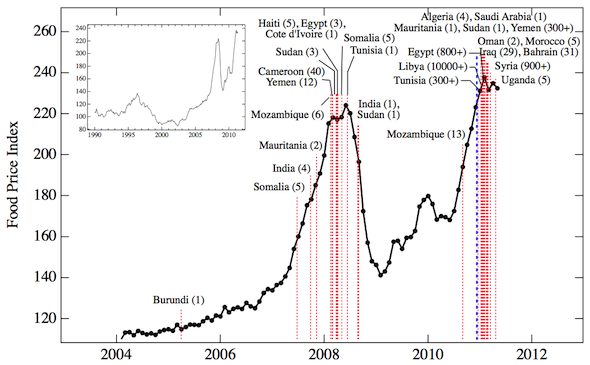

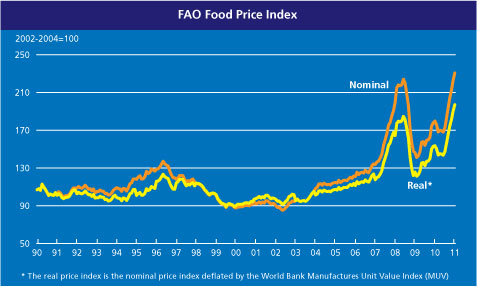

The FAO report – The World Food Situation – reports that world food prices surged to a new historic peak in January, for the seventh consecutive month. The FAO Food Price Index (below) is a commodity basket that regularly tracks monthly changes in global food prices.

This is the highest level (both in real and nominal terms) since FAO started measuring food prices in 1990.

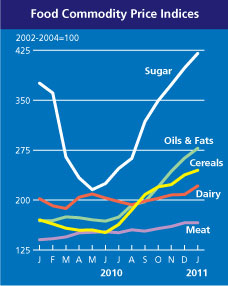

As we can see from the chart on the right, the price of individual commodities that comprise the index – meat, dairy, cereals, oil and fats, and sugar – are all on the rise.

As we can see from the chart on the right, the price of individual commodities that comprise the index – meat, dairy, cereals, oil and fats, and sugar – are all on the rise.

Global food prices have exceeded their pre-recession price levels. Some of this is due to the price of petroleum returning to pre-recession levels. About 17% of all petroleum production is consumed for food production. Petroleum is a key ingredient in the manufacture of fertilizer and pesticides, and sources energy for irrigation, food transport, etc. Note how the Food Price Index closely parallels the price of oil.

In addition, climate change is driving an increase in extreme weather, including record heat during growing seasons, record flooding, and extreme rain.

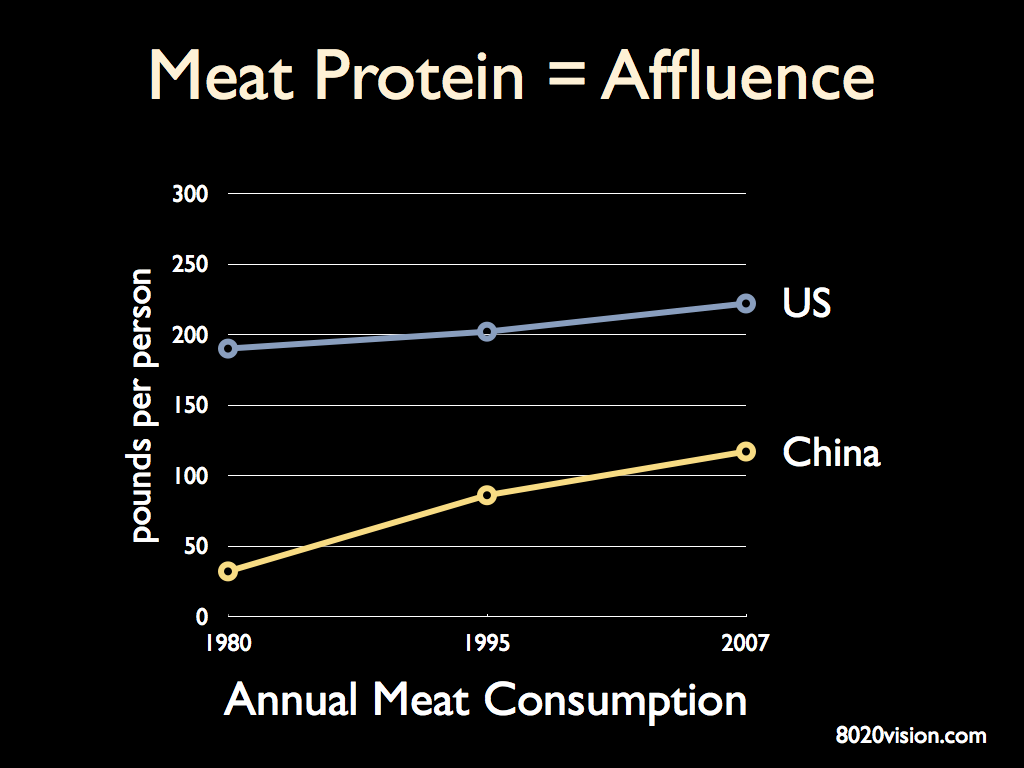

And as nations move up the affluence curve, their consumption of food increases, creating rising demand from a limited supply. As Julian Cribb, author of The Coming Famine: The Global Food Crisis and What We Can Do to Avoid It, astutely points out – as developing nations become more affluent, they consume more protein, in the form of fish, meat, milk, eggs, etc. For an example from China, read the article that appeared in The Financial Times today: Chinese Corn Imports Forecast to Soar. Note the mention of corn for meat production.

Protein is usually produced with grain, and it is an inefficient process:

- It takes 1,ooo tons of water to produce a ton of grain

- It takes about 15 pounds of grain to produce a pound of beef

- So, it takes about 5,200 gallons of water to produce a pound of beef

As our population increases, and as each nation seeks affluence, food will become a major factor in the stability of all nations, not just the rotting authoritarian regimes of the world.

Related Articles

Climate Change May Reduce Protein in Crops

Julian Cribb says:

An excellent piece, Jay.

The main reason the Roman Empire disintegrated was two epidemics of measles (far more deadly then than now)which killed off many of the farmers in the Med basin. As a result the Roman economy took a major hit, 52 legions went un-paid or underpaid and a number of them defected to join forces with the border tribes, notably the Ostrogoths. It’s a clear case of lack of sustenance causing the failure of a governmental system, though the French and Russian revolutions are more recent in our memory. Nations where agriculture makes up a significant slice of the economy are especially vulnerable to this type of collapse.

Unfortunately the hike in global food prices does not mean farmers are more profitable, as fuel, fertiliser and other inputs have risen as fast or even faster. This points to further disinvestment in agriculture globally and accelerating degradation of the farming resource base.

Since agriculture is the cornerstone without which you cannot build a long-term stable government, this in turn points to an increase in the amount of failed states over coming decades, especially as climate impacts intensify. And failed states cost all of us, regardless of where we live, through knock-on impacts on trade, refugeeism and war.

jaykimball says:

Thanks Julian.

I appreciate your expanding the Gestalt of the piece – deepening the connections to farmers, climate change, geopolitical implications, refugees, war,…

It’s all interwoven in a complex Gordian knot.

“We are shaping the world faster than we can change ourselves, and we are applying to the present the habits of the past.”

jaykimball says:

Thomas Friedman op-ed on Egypt is worth a read: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/06/opinion/06friedman.html?ref=opinion

Some notable quotes that relate to the article above:

“China and the whole Asian-led developing world’s rising consumption of meat, corn, sugar, wheat and oil certainly is. The rise in food and gasoline prices that slammed into this region in the last six months clearly sharpened discontent with the illegitimate regimes — particularly among the young, poor and unemployed.”

“Add in rising food prices, and the diffusion of Twitter, Facebook and texting, which finally gives them a voice to talk back to their leaders and directly to each other, and you have a very powerful change engine.”

Emily says:

This paints a real, but very grim, picture

jaykimball says:

Exploring the question of “Who is next?” – The Economist weighs with thoughts about which nations are most vulnerable revolution:

http://www.economist.com/node/18065663

John Dyer says:

Terrific article, Jay. Well structured flow of logic. I was suprised the US scored an 8.2 on the democracy scale. I would have thought we would come out lower when you consider the factor that money plays in our government.

jaykimball says:

Agreed.

Charles Blow is using the Economist Democracy Index 2010.

I note that many of the commenters to Blow’s op-ed had similar concerns. Quoting:

“Interesting chart. I guess I’m baffled that the US is considered a “Full Democracy.” …unless voting for the interests of the rich is now the new definition of a democracy. I’m not feeling it. Check out the “Income Inequality” column. Our system rewards speculation and greed over hard work and ethical behavior.”

“Income inequality is a major factor and is a major problem in the USA. I don’t think the USA has a full democracy anymore because of the power of money to propagandize. Also, the elected governmental officials are so influenced by lobbyists, and poor people don’t have the luxury to afford lobbyists to promote their causes.”

“Hmmm…So you say the main difference in the USA is that we have a “full democracy?” Say what? Since when? I would say we have a “corporate state,” and I think many others would agree. Our income equality is appalling.”

In Ill Fares the Land, by Tony Judt, (http://tinyurl.com/ill-fares-the-land ) there is some excellent data on income inequality and social mobility, which are good measures of the strength of democracy in a nation. Needless to say the US ranks near the bottom of developed nations and modern democracies.

jaykimball says:

Global food scarcity seems to be on peoples minds this week. Paul Krugman at the Times talked about food and climate change. See:

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/07/opinion/07krugman.html?_r=1&hp

Djuna says:

Great article Jay. Along with internet penetration it would be interesting to compare the influence of the media in each country and to what degree public opinion is shaped by media reporting. Also, the percentage of independent media.

jaykimball says:

Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz has an outstanding cogent article at Vanity Fair this week. Read every word. See:

http://www.vanityfair.com/society/features/2011/05/top-one-percent-201105

Here’s an excerpt:

“Alexis de Tocqueville once described what he saw as a chief part of the peculiar genius of American society—something he called “self-interest properly understood.” The last two words were the key. Everyone possesses self-interest in a narrow sense: I want what’s good for me right now! Self-interest “properly understood” is different. It means appreciating that paying attention to everyone else’s self-interest—in other words, the common welfare—is in fact a precondition for one’s own ultimate well-being. Tocqueville was not suggesting that there was anything noble or idealistic about this outlook—in fact, he was suggesting the opposite. It was a mark of American pragmatism. Those canny Americans understood a basic fact: looking out for the other guy isn’t just good for the soul—it’s good for business.”

Anonymous says:

It would have been interesting to include housing costs because, while people in the US spend a lower percentage of their income on food than people in other countries spend, I’ll bet the US’s higher housing costs negate that apparent advantage.

jaykimball says:

Here’s Jeffrey Sachs talking about the Occupy Wall Street protests, and comparing them with various uprisings around the world. I find him cogent, even-handed and helping put this into perspective. The reporters interviewing him are asking good questions, finally.

Kal Palnicki says:

Flawed democracy?? Is there an unflawed one anywhere? If so, where and why are we all unaware of it?

Kal Palnicki says:

You’d be wrong. Some nations have massive housing costs like Japan, Israel and others where land is at a premium and money is not scarce.