Subsidies and tax breaks are a tried and true way of helping a developing industry get up on its feet.

One of the strategies to accelerate a transition to cleaner greener renewable energy sources is to subsidize research development, and production of renewable energy sources, such as wind power, solar power, geothermal, etc.

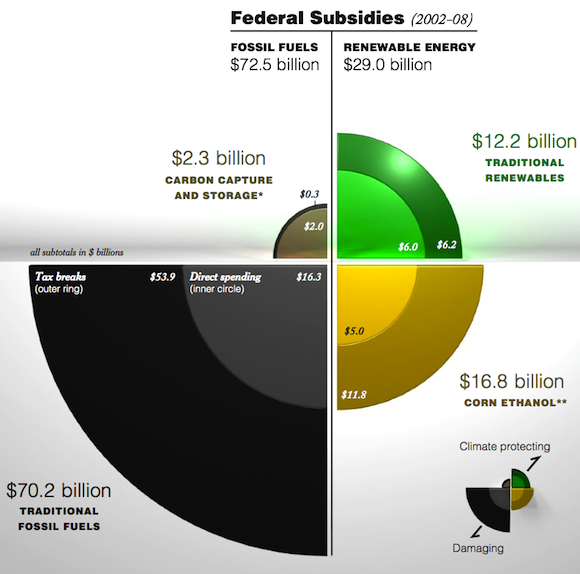

Free market advocates often say that the emerging renewable energy industry should not be subsidized. What is not widely know though, is that subsidies for well established fossil fuels exceed renewables by almost six to one.

Research by the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and the Environmental Law Institute reveals that the lion’s share of energy subsidies supported energy sources that emit high levels of greenhouse gases (GHGs). The study, which reviewed fossil fuel and energy subsidies for Fiscal Years 2002-2008, showed that the federal government spent about $70 billion on the fossil fuel industry, and about $12 billion on renewables. As the report points out:

Moreover, just a handful of tax breaks make up the largest portion of subsidies for fossil fuels, with the most significant of these, the Foreign Tax Credit, supporting the overseas production of oil. More than half of the subsidies for renewables are attributable to corn-based ethanol, the use of which, while decreasing American reliance on foreign oil, has generated concern about climate effects.These figures raise the question of whether scarce government funds might be better allocated to move the United States towards a low-carbon economy.

N.B. Carbon capture and storage is a developing technology that would allow coal-burning utilities to capture and store their carbon dioxide emissions. Although this technology does not make coal a renewable fuel, if successful it would reduce greenhouse gas emissions compared to coal plants that do not use this technology. The production and use of corn ethanol can generate significant greenhouse gas emissions. Recognizing that the production and use of corn-based ethanol may generate significant greenhouse gas emissions, the data depict renewable subsidies both with and without ethanol subsidies.

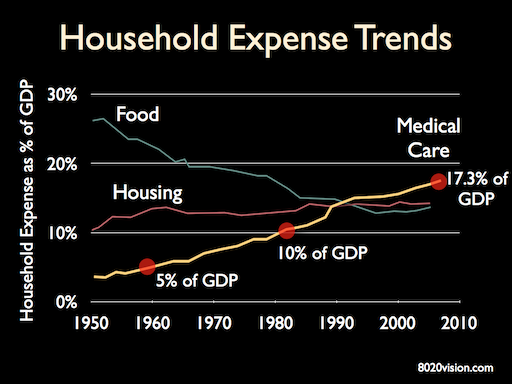

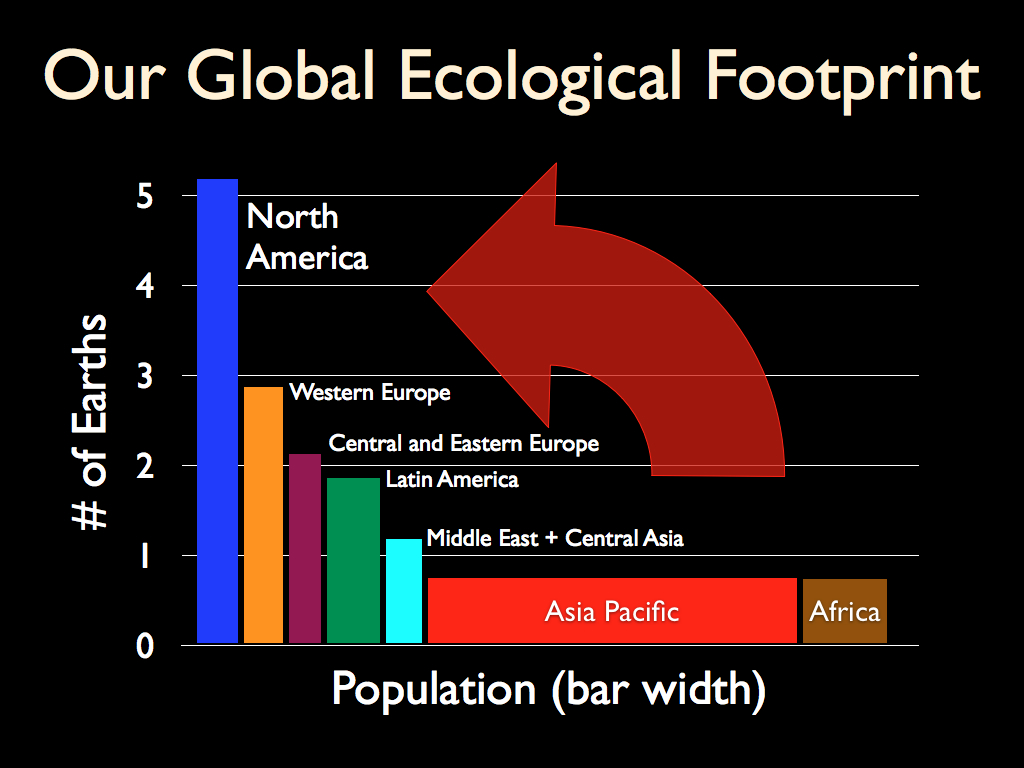

Fossil fuel extraction is increasingly toxic (e.g. fracking poisons public water systems) and environmentally destructive (e.g. gulf oil “spill”). And fossil fuel production seems to be hitting a Peak Oil wall. As production lags demand, we should expect oil and gas prices to rise precipitously. Subsidizing oil keeps us addicted to it.

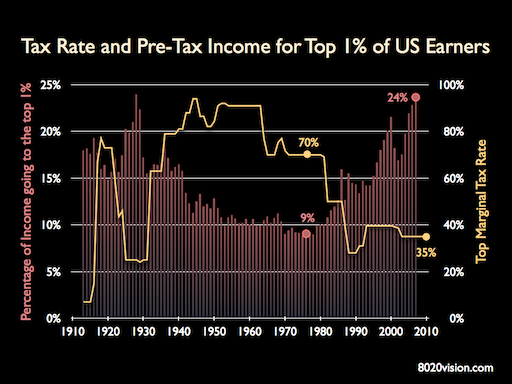

Three of the top 5 biggest companies in the world are oil companies (Exxon, BP, Royal Dutch Shell). Rather than subsidize Big Oil profits and foreign oil nations, we should be taxing fossil fuels to reduce their use. Tax what we want to reduce, and subsidize what we want to increase. Tax what harms us, and subsidize what helps us. Use the taxes to fund R&D and development of a world class alternative energy industry.

Obviously, that means politicians will need to resist the monied special interests of the Big Oil lobby.

What would you like to see your politicians do?

Recommended Reading

Top Business Leaders Deliver Clean Energy Plan by Jay Kimball