With Bush-era tax cuts about to expire, a lot of attention is being focused on extending tax cuts for the rich – suggesting it will help the economy grow. Frank Rich, in his weekly op-ed piece at the New York Times, deconstructs that idea and examines the issue through the lens of income inequality.

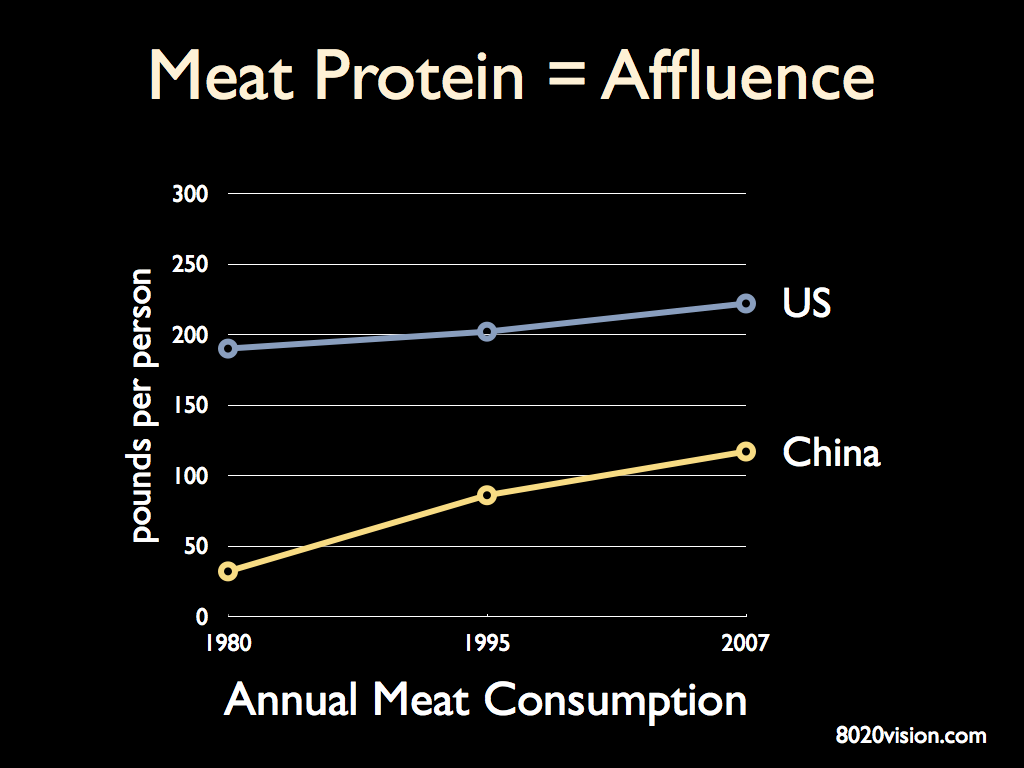

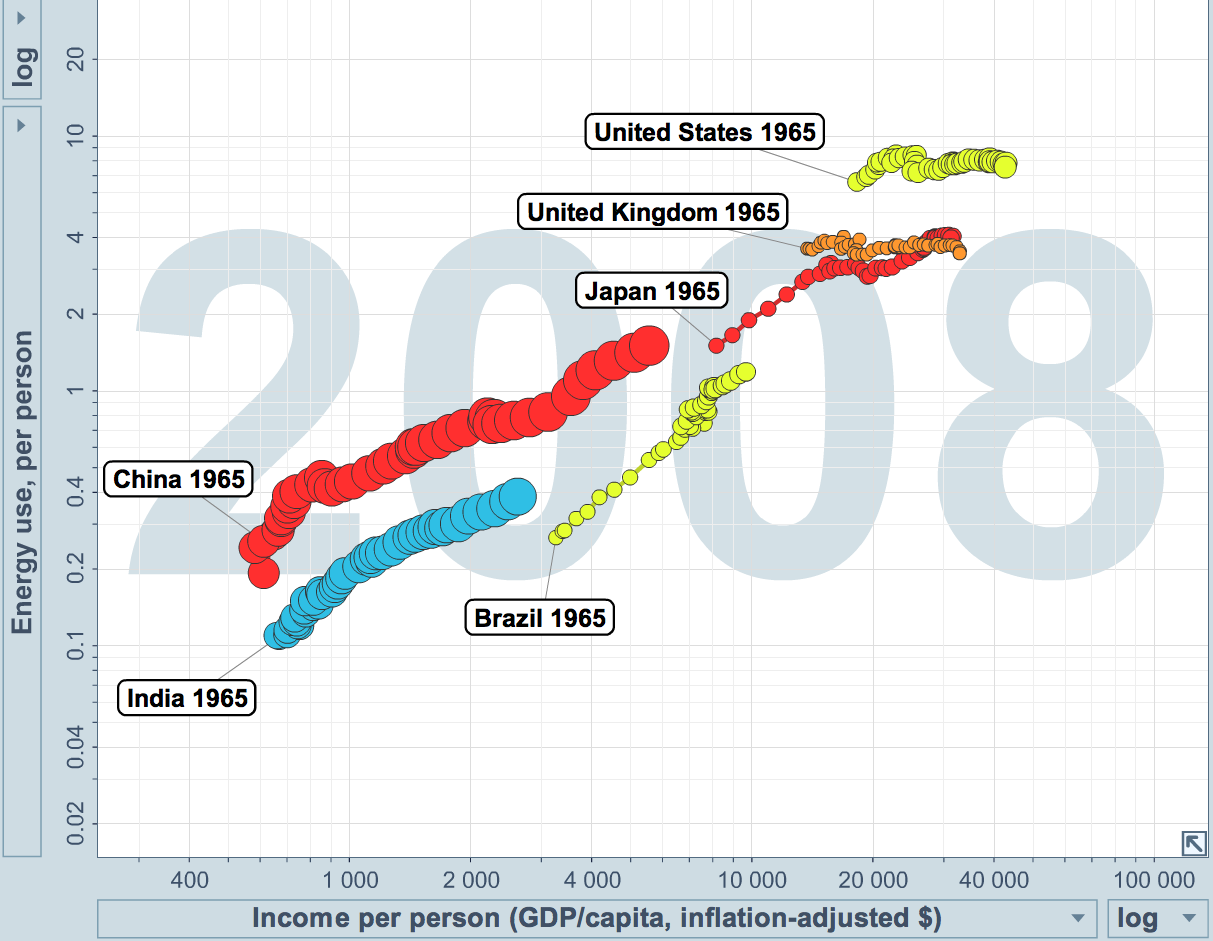

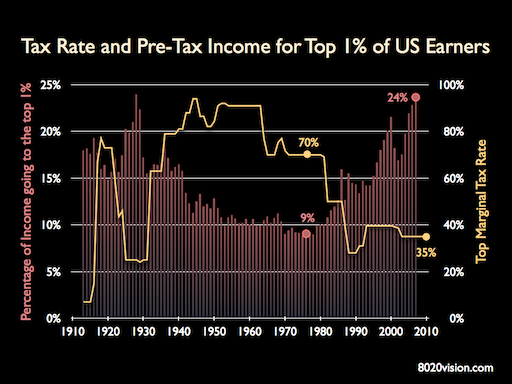

The top 1 percent of American earners now have tax rates half what they were in the 1970s. And they took in 23.5 percent of the nation’s pre-tax income in 2007 — up from less than 9 percent in 1976. During the boom years of 2002 to 2007, that top 1 percent’s pre-tax income increased an extraordinary 10 percent every year. In that same period, the average inflation-adjusted hourly wage went down more than 7 percent and the poverty rate rose.

The rich have been getting richer as their tax rate has steadily eased. And they are taking the added wealth and using it to influence public policy, to the detriment of the middle class.

“How can hedge-fund managers who are pulling down billions sometimes pay a lower tax rate than do their secretaries?” ask the political scientists Jacob S. Hacker (of Yale) and Paul Pierson (University of California, Berkeley) in their deservedly lauded new book, Winner-Take-All Politics

…Inequality is instead the result of specific policies, including tax policies, championed by Washington Democrats and Republicans alike as they conducted a bidding war for high-rolling donors in election after election.

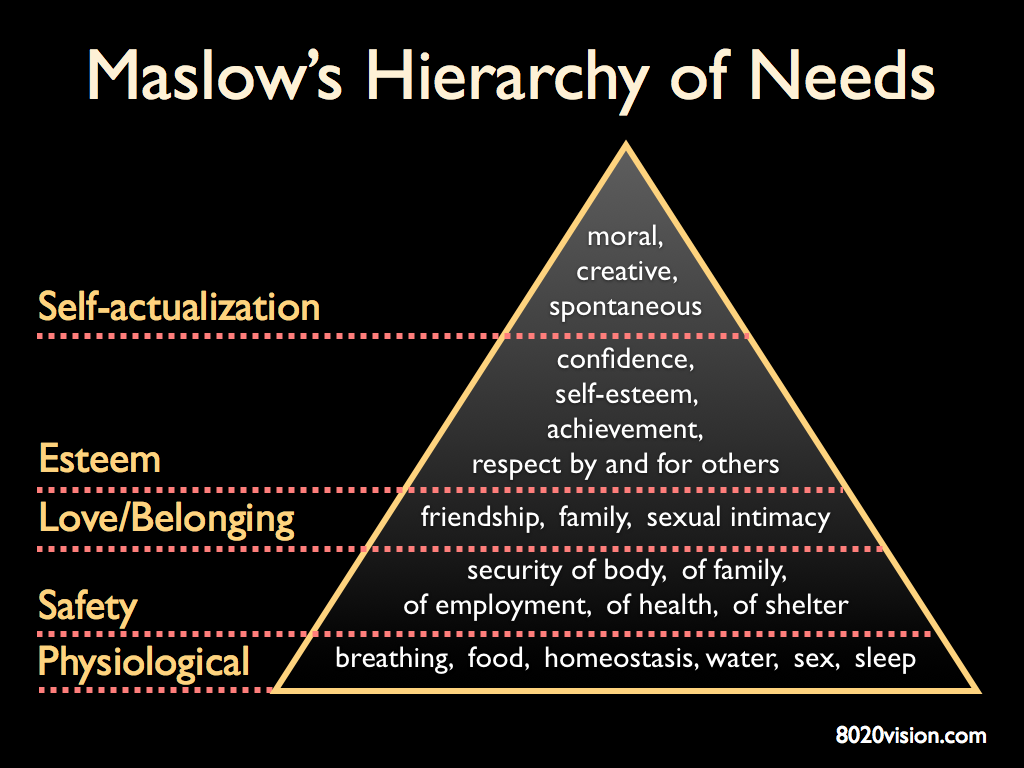

And as Frank Rich points out, the American Dream is not well. Rather than middle class wage earners moving up the ladder, there are less and less people becoming wealthy, and more and more of the wealthy simply becoming wealthier.

Nor are the superrich helping to further the traditional American business culture that inspires and encourages those with big ideas and drive to believe they can climb to the top. Robert Frank, the writer who chronicled the superrich in the book Richistan, recently analyzed the new Forbes list of the 400 richest Americans for The Wall Street Journal and found a “hardening of the plutocracy” and scant mobility. Only 16 of the 400 were newcomers — as opposed to an average of 40 to 50 in recent years — and they tended to be in industries like coal, natural gas, chemicals and casinos rather than forward-looking businesses involving the Green Economy, tech or biotechnology. This is “not exactly the formula for America’s vaunted entrepreneurial wealth machine,” Frank wrote.

Those in the higher reaches aren’t investing in creating new jobs even now, when the full Bush tax cuts remain in effect, so why would extending them change that equation? American companies seem intent on sitting on trillions in cash until the economy reboots. Meanwhile, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office ranks the extension of any Bush tax cuts, let alone those to the wealthiest Americans, as the least effective of 11 possible policy options for increasing employment.

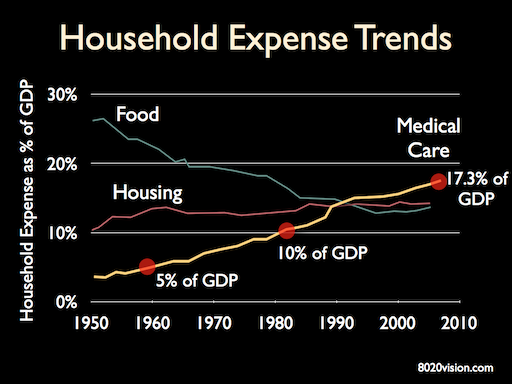

The middle class is experiencing the twin stress of falling income and increasing expenses. The most significant household expense is healthcare.

Healthcare costs represent a stunning 17% of GDP. Politicians that cut taxes without a plan for how to cover the costs of Medicare are dooming the middle class to a future of just working to pay for out of control medical costs.

With the Income Inequality Gap growing, perhaps we can understand why, during the 2010 midterm election, only 40 percent of voters approved of an extension of all Bush tax cuts.

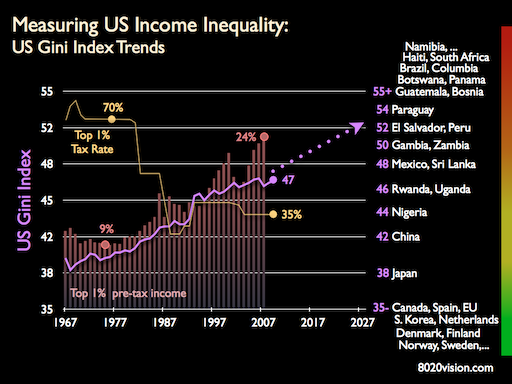

Measuring Income Inequality: The Gini Index

No society can sustain itself without a healthy middle class. No healthy society ignores it’s poor. As income inequality increases, social stability decreases.

Economists, the US Department of Labor, and analysts at the CIA, track Income Inequality using a metric known as the Gini Index (also known as the Gini Coefficient).

It is one of the essential metrics in the Political Instability Index, which is used to assess the level of threat posed to governments by social unrest. Zimbabwe, Chad and Congo rank most unstable, with Canada, Denmark, and Norway ranking most stable. Notably, the US, once the standard-setter of a stable democracy and middle class, has quickly fallen to an underwhelming rank 110 out of 165 countries.

The Gini Index is proportional to the Income Inequality of a nation. A Gini Index value of 0 indicates equal income for all earners. A Gini Index of 100 means that one person had all the income and nobody else had any.

A lower Gini Index indicates more equitable distribution of wealth in a society, while higher Gini Coefficients mean that wealth is concentrated in the hands of fewer people. Societies with high Gini Index tend to be unstable.

The chart below shows the historic trend of the Gini Index for the US, with tax rate and pre-tax income data for the top 1% of US earners in the background. On the right are various countries, with their associated Gini Index. Developed nations that take care of their own tend to have Gini indexes in the twenties and 30s. The US Gini Index is on track to breach 50 by the end of the decade, putting the US in the dubious country club of third world dictatorships and failing nations.

If you are a business leader, ask yourself, “Do I want to be living and building a business in world like that?” If the answer is NO, think about what public policy you are supporting through your contributions to politicians, associations and the Chamber of Commerce. Are the politicians you are supporting interested in a healthy middle class?

Business paid billions of dollars to politicians in the 2010 election. Paraphrasing W. W. Jacobs in his classic cautionary tale, The Monkey’s Paw, “Be careful what you wish for, you might get it.”

Recommended Reading

Winner-Take-All Politics by Jacob S. Hacker and Paul Pierson

Richistan by Robert Frank

The Spirit Level by Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett

The Monkey’s Paw By W.W. Jacobs

The Tyranny of Dead Ideas by Matt Miller

Rethinking the Measure of Growth by Jay Kimball

Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz on Sustainability and Growth by Jay Kimball

The Bush Tax Cuts and the Economy by The Congressional Research Service