Jeremy Grantham, savvy dean of US money management, has boiled climate change down to thirteen essentials.

Jeremy Grantham is Chairman of the Board of Grantham Mayo Van Otterloo (GMO), a Boston-based asset management firm. GMO is one of the largest managers of such funds in the world. Grantham is regarded as a highly knowledgeable investor in various stock, bond, and commodity markets, and is particularly noted for his prediction of various bubbles.

Grantham’s Everything You Need to Know About Global Warming in 5 Minutes appeared in GMO’s Quarterly Letter, published July 2010.

Everything You Need to Know About Global Warming in 5 Minutes

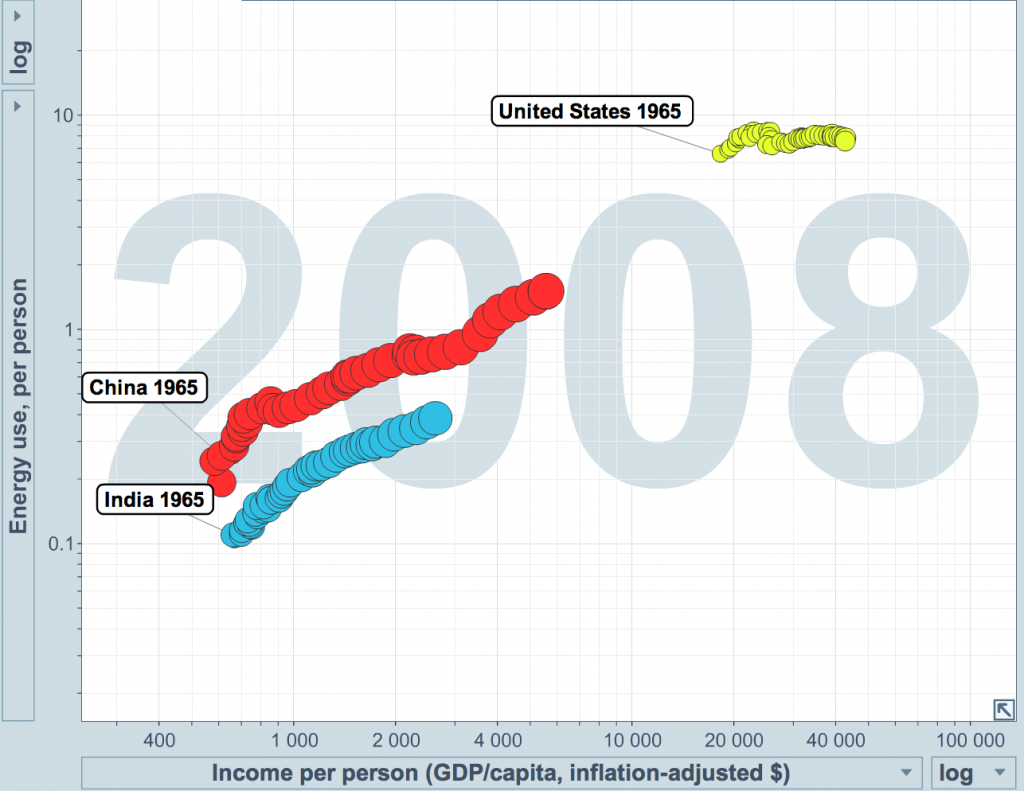

- The amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere, after at least several hundred thousand years of remaining within a constant range, started to rise with the advent of the Industrial Revolution. It has increased by almost 40% and is rising each year. This is certain and straightforward.

- One of the properties of CO2 is that it creates a greenhouse effect and, all other things being equal, an increase in its concentration in the atmosphere causes the Earth’s temperature to rise. This is just physics. (The amount of other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, such as methane, has also risen steeply since industrialization, which has added to the impact of higher CO2 levels.)

- Several other factors, like changes in solar output, have major influences on climate over millennia, but these effects have been observed and measured. They alone cannot explain the rise in the global temperature over the past 50 years.

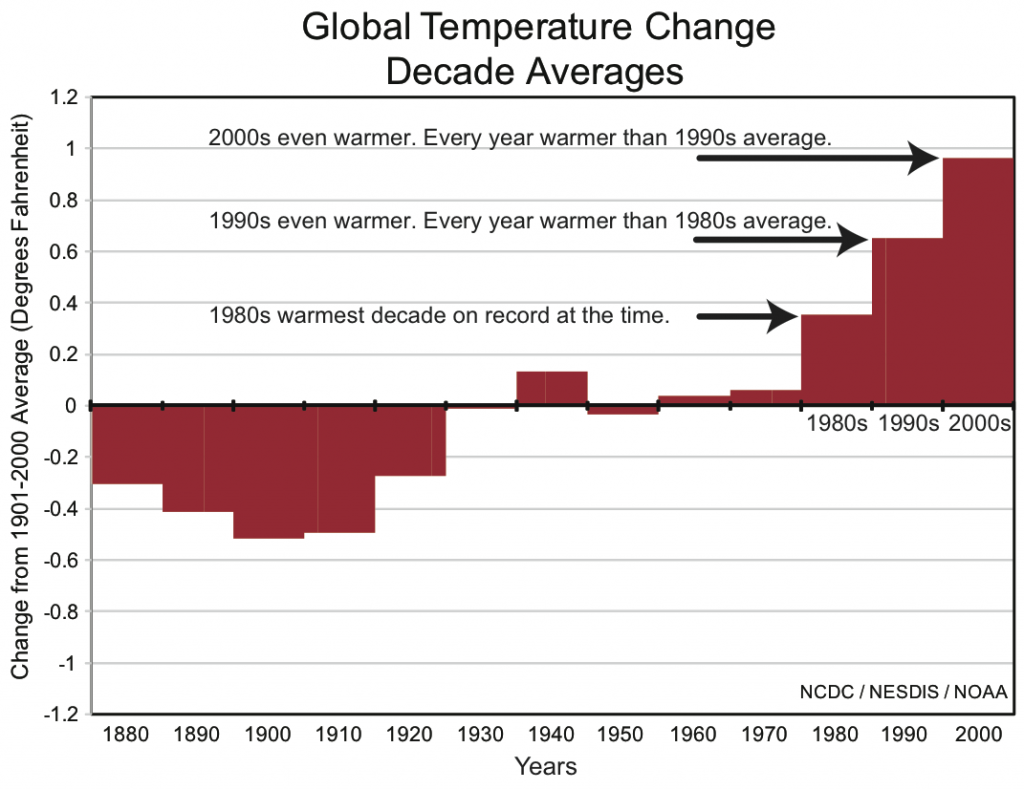

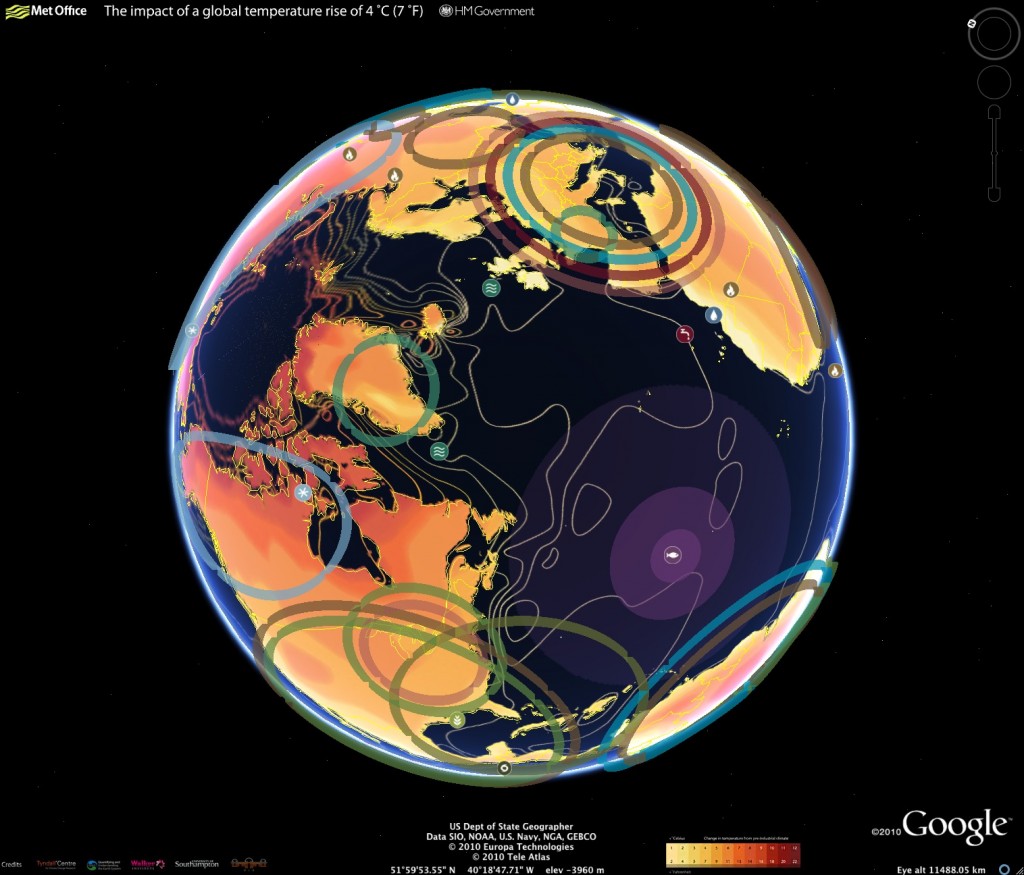

- The uncertainties arise when it comes to the interaction between greenhouse gases and other factors in the complicated climate system. It is impossible to be sure exactly how quickly or how much the temperature will rise. But, the past can be measured. The temperature has indeed steadily risen over the past century while greenhouse gas levels have increased. But the forecasts still range very widely for what will happen in the future, ranging from a small but still potentially harmful rise of 1 to 2 degrees Fahrenheit to a potentially disastrous level of +6 to +10 degrees Fahrenheit within this century. A warmer atmosphere melts glaciers and ice sheets, and causes global sea levels to rise. A warmer atmosphere also contains more energy and holds more water, changing the global occurrences of storms, floods, and other extreme weather events.

- Skeptics argue that this wide range of uncertainty about future temperature changes lowers the need to act: “Why spend money when you’re not certain?” But since the penalties can rise at an accelerating rate at the tail, a wider range implies a greater risk (and a greater expected value of the costs.) This is logically and mathematically rigorous and yet is still argued.

- Pascal asks the question: What is the expected value of a very small chance of an infinite loss? And, he answers, “Infinite.” In this example, what is the cost of lowering CO2 output and having the long-term effect of increasing CO2 turn out to be nominal? The cost appears to be equal to foregoing, once in your life, six months’ to one year’s global growth – 2% to 4% or less. The benefits, even with no warming, include: energy independence from the Middle East; more jobs, since wind and solar power and increased efficiency are more labor-intensive than another coal-fired power plant; less pollution of streams and air; and an early leadership role for the U.S. in industries that will inevitably become important. Conversely, what are the costs of not acting on prevention when the results turn out to be serious: costs that may dwarf those for prevention; and probable political destabilization from droughts, famine, mass migrations, and even war. And, to Pascal’s real point, what might be the cost at the very extreme end of the distribution: definitely life changing, possibly life threatening.

- The biggest cost of all from global warming is likely to be the accumulated loss of biodiversity. This features nowhere in economic cost-benefit analysis because, not surprisingly, it is hard to put a price on that which is priceless.

- A special word on the right-leaning think tanks: As libertarians, they abhor the need for government spending or even governmental leadership, which in their opinion is best left to private enterprise. In general, this may be an excellent idea. But global warming is a classic tragedy of the commons – seeking your own individual advantage, for once, does not lead to the common good, and the problem desperately needs government leadership and regulation. Sensing this, these think tanks have allowed their drive for desirable policy to trump science. Not a good idea.

- Also, I should make a brief note to my own group – die hard contrarians. Dear fellow contrarians, I know the majority is usually wrong in the behavioral jungle of the stock market. And Heaven knows I have seen the soft scientists who lead finance theory attempt to bully their way to a uniform acceptance of the bankrupt theory of rational expectations and market efficiency. But climate warming involves hard science. The two most prestigious bastions of hard science are the National Academy in the U.S. and the Royal Society in the U.K., to which Isaac Newton and the rest of that huge 18th century cohort of brilliant scientists belonged. The presidents of both societies wrote a note recently, emphasizing the seriousness of the climate problem and that it was man- made. (See the attachment to last quarter’s Letter.) Both societies have also made full reports on behalf of their membership stating the same. Do we believe the whole elite of science is in a conspiracy? At some point in the development of a scientific truth, contrarians risk becoming flat earthers.

- Conspiracy theorists claim to believe that global warming is a carefully constructed hoax driven by scientists desperate for … what? Being needled by nonscientific newspaper reports, by blogs, and by right-wing politicians and think tanks? Most hard scientists hate themselves or their colleagues for being in the news. Being a climate scientist spokesman has already become a hindrance to an academic career, including tenure. I have a much simpler but plausible “conspiracy theory”: that fossil energy companies, driven by the need to protect hundreds of billions of dollars of profits, encourage obfuscation of the inconvenient scientific results.

- Why are we arguing the issue? Challenging vested interests as powerful as the oil and coal lobbies was never going to be easy. Scientists are not naturally aggressive defenders of arguments. In short, they are conservatives by training: never, ever risk overstating your ideas. The skeptics are far, far more determined and expert propagandists to boot. They are also well funded. That smoking caused cancer was obfuscated deliberately and effectively for 20 years at a cost of hundreds of thousands of extra deaths. We know that for certain now, yet those who caused this fatal delay have never been held accountable. The profits of the oil and coal industry make tobacco’s resources look like a rounding error. In some notable cases, the obfuscators of global warming actually use the same “experts” as the tobacco industry did! The obfuscators’ simple and direct motivation – making money in the near term, which anyone can relate to – combined with their resources and, as it turns out, propaganda talents, have meant that we are arguing the science long after it has been nailed down. I, for one, admire them for their P.R. skills, while wondering, as always: “Have they no grandchildren?”

- Almost no one wants to change. The long-established status quo is very comfortable, and we are used to its deficiencies. But for this problem we must change. This is never easy.

- Almost everyone wants to hear good news. They want to believe that dangerous global warming is a hoax. They, therefore, desperately want to believe the skeptics. This is a problem for all of us.

Postscript

Global warming will be the most important investment issue for the foreseeable future. But how to make money around this issue in the next few years is not yet clear to me. In a fast-moving field rife with treacherous politics, there will be many failures. Marketing a “climate” fund would be much easier than outperforming with it.