Lat year I posted an article (Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz on Sustainability and Growth) about an interview with economics Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz at the Asia Society in New York City. Stiglitz talked about how “what we measure determines what we grow” and the dramatic negative side-effects a metric like GDP can have on societal well-being.

Today, Wayne Arnold at The New York TImes builds on this idea in his article Rethinking the Measure of Growth.

Highlights from NY Times Article

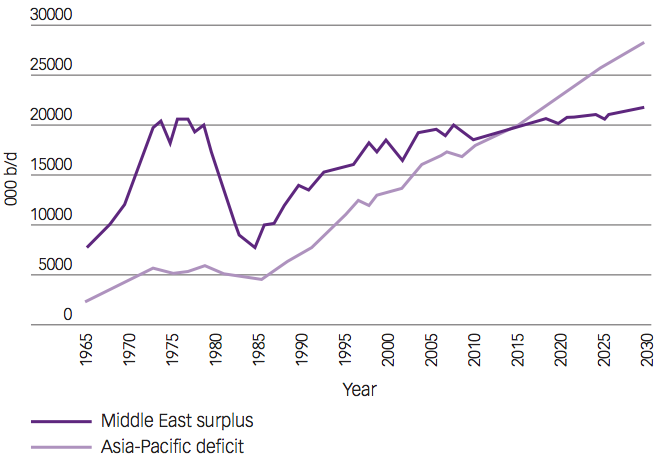

- The quest for more plentiful and less expensive oil for fast-growing Asian economies has also brought a wave of offshore drilling from India and the Gulf of Thailand, to Vietnam and Bohai Bay, on the northeast coast of China.

- In considering this risk and the increasing evidence of the toll that rapid economic development is already taking on Asia’s environment, economists and other experts in Asia have taken up the call to re-examine the prominence of economic growth as a measure of policy success, particularly the use of gross domestic product.

- Asian governments have become particularly enthralled with gross domestic product (GDP) statistics for validation, becoming what Vishakha Desai, the president and chief executive of the Asia Society in New York, has called “G.D.P. junkies.”

For local officials in China, gross domestic product was, until recently, more than just a barometer for gauging policies, it was the measuring stick against which their futures in the ruling Communist Party were determined. Economic growth still ranks as one of the chief criteria for determining party promotions, according to Tan Kong Yam, an economics professor at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore who offers a course for mayors from China.

For such officials, “there is an enormous incentive to promote investments and industrial production,” he said. “This explains why there’s enormous pollution.”

- Gross domestic product has come in for some particularly hard knocks since the global financial crisis, notably after a report last year whose co-author was Joseph E. Stiglitz, a Nobel laureate in economics, that said reliance on gross domestic product had blinded governments to the increasing risks in the world economy since 2004.

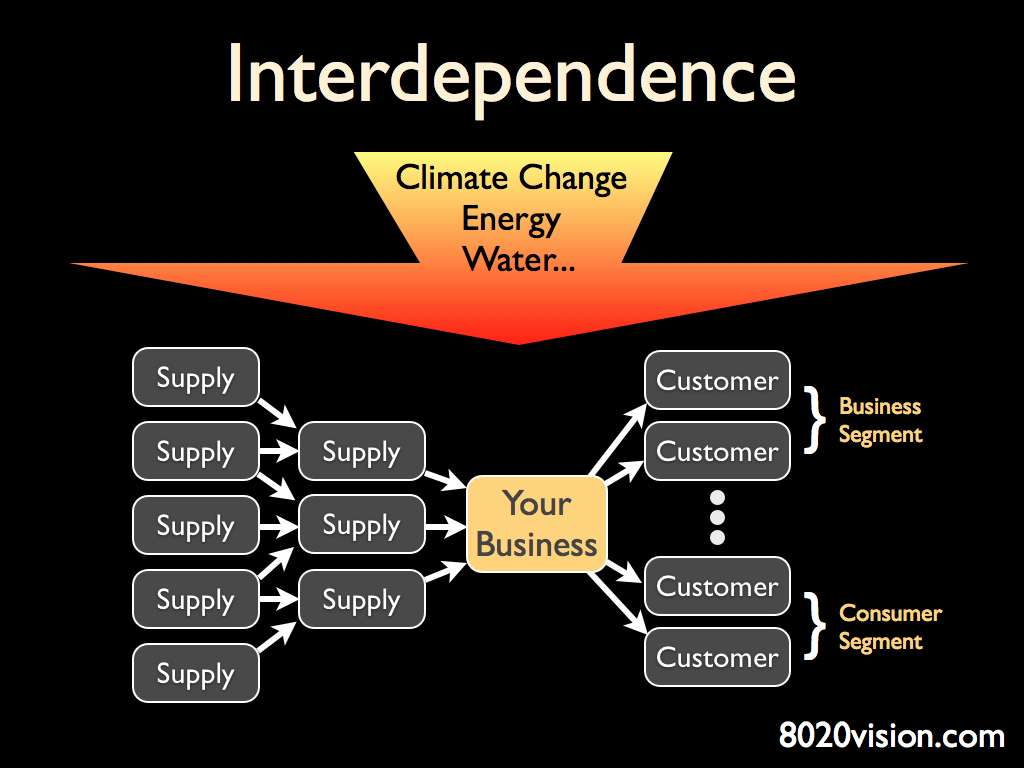

- Overlooking that risk has possibly cost future economic growth, the report said, and has contributed to a looming environmental crisis.

“Market prices are distorted by the fact that there is no charge imposed on carbon emissions,” the report said. “Clearly, measures of economic performance that reflected these environmental costs might look markedly different from standard measures.”

Economists in Asia say the debate about gross domestic product misses the point. Gross domestic product as a statistic is sound, they say; what is wrong is the fascination in government with what it measures — the sum total of a nation’s annual production.

“The problem is not G.D.P.,” said Bhanoji Rao, a visiting economics professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy in Singapore. “The problem is the culture of consumption.”

- Mr. Rao is part of a growing body of economists, largely in academia, who question whether rapid economic growth rates in Asia — from the 10.3 percent expansion in giant-but-poor China to an expected 15 percent growth this year in tiny-but-rich Singapore — are necessarily producing a happier, healthier Asia.

- Some Asian governments, China’s included, have been trying to recalibrate gross domestic product to include the cost of growth to the environment, creating a green gross domestic product. Such efforts, said Mr. Tan, the Nanyang professor, have been frustrated by the difficulty in determining the future cost of environmental destruction.

- What is needed instead, some economists say, is a wholesale re-examination of development’s goals. “There needs to be an internal debate within the developing countries about what is the path of development we want to have,” Mr. Rao said.

Andy Xie, a private economist in Shanghai, has long argued that the 1.3 billion people in China cannot realistically hope to live like Americans.

“That statement is truer than ever,” he said.

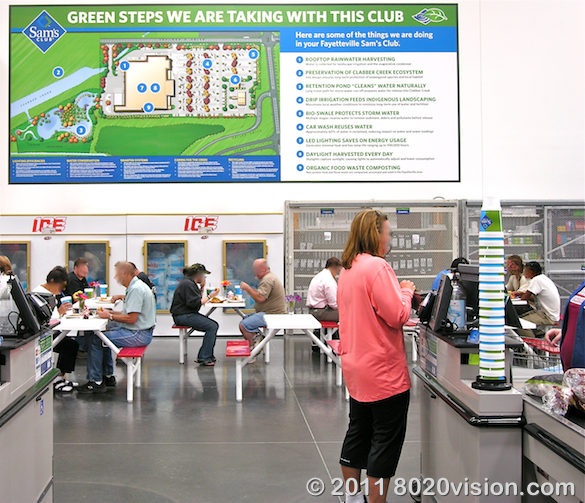

Beijing, at least, appears to have gotten the message, if its investments in green technology and public transportation are anything to go by. The Communist Party has also revised the promotion criteria for officials so that environmental conditions are included along with gross domestic product.

But economists like Mr. Xie and Mr. Rao warn that even with greener development, the result may still be the same if the goal remains an American-style standard of living. Asia may instead need to carve out a vastly different vision of prosperity that does not rely on ever-increasing levels of material consumption.